|

New

Releases |

January 16, 2026

|

January 9, 2026

|

January 2, 2026

|

December 26, 2025

|

December 19, 2025

|

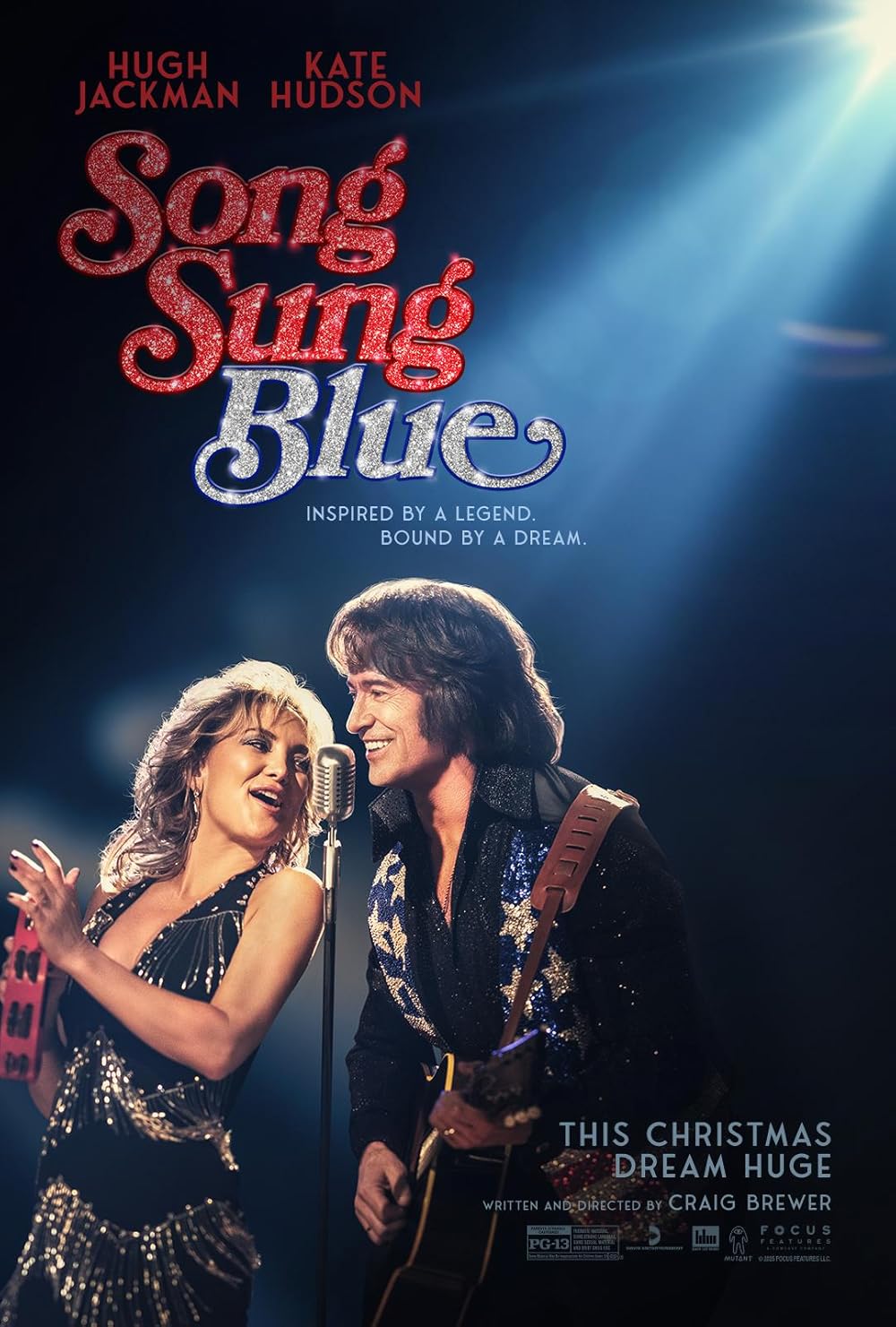

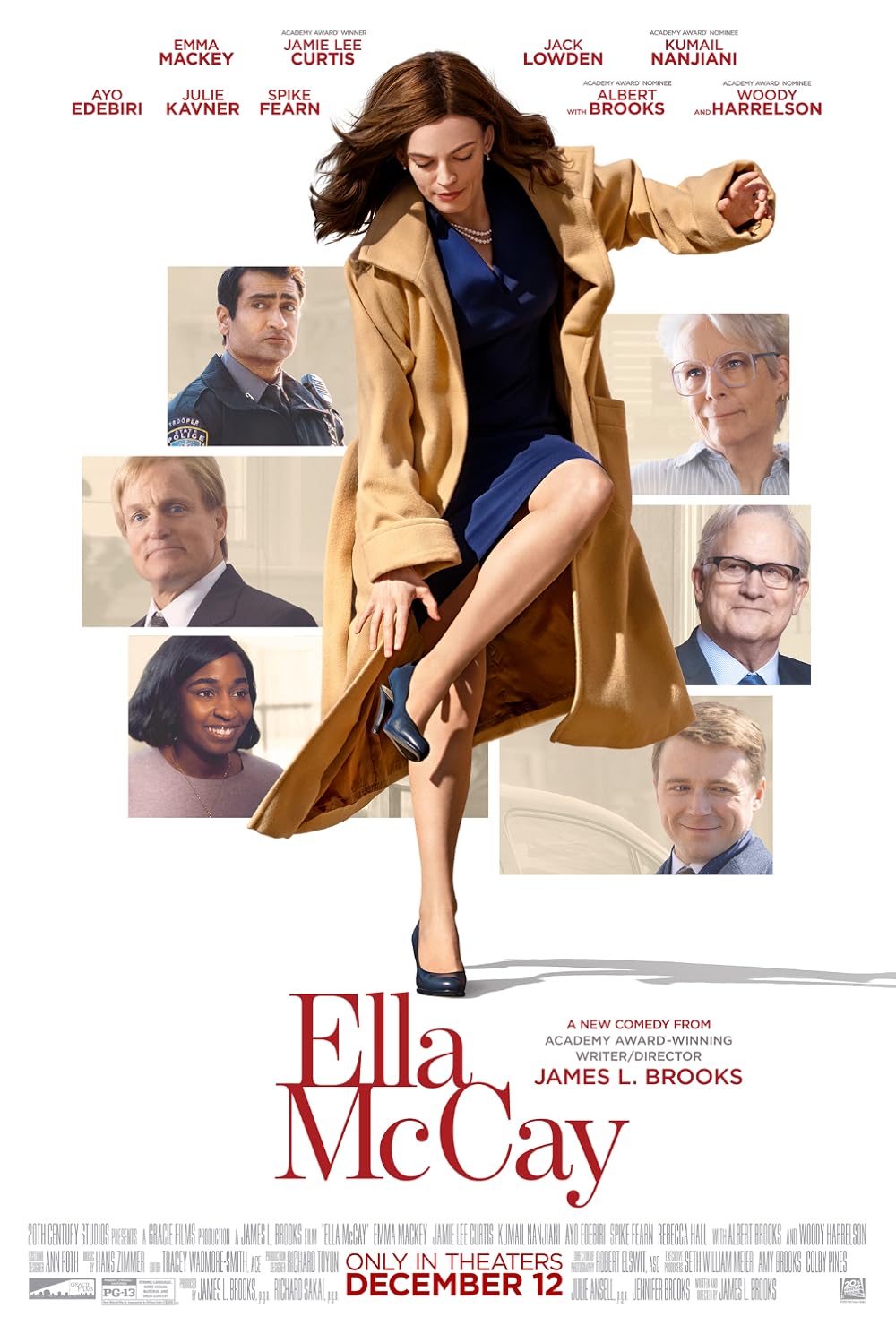

December 12, 2025

|

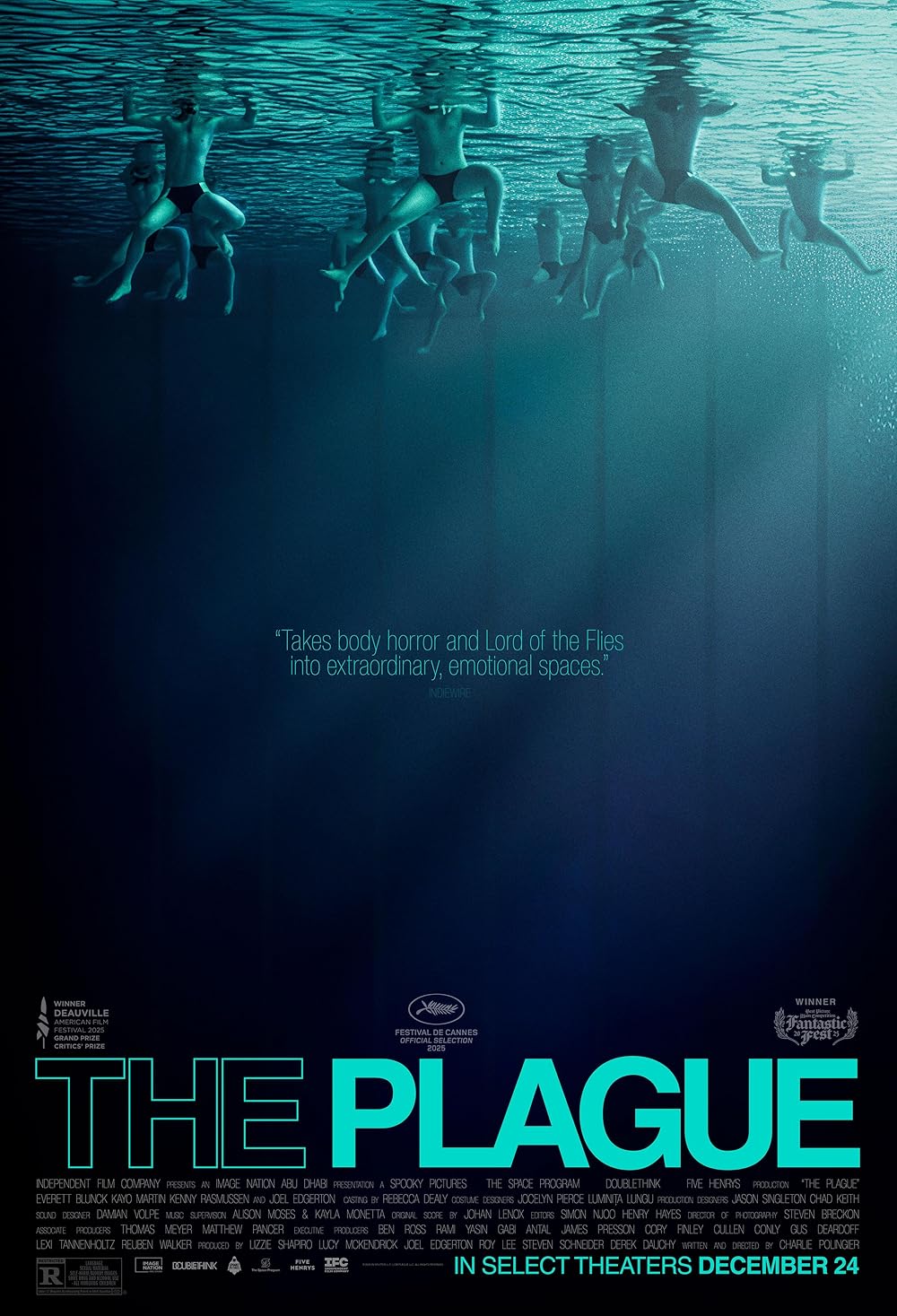

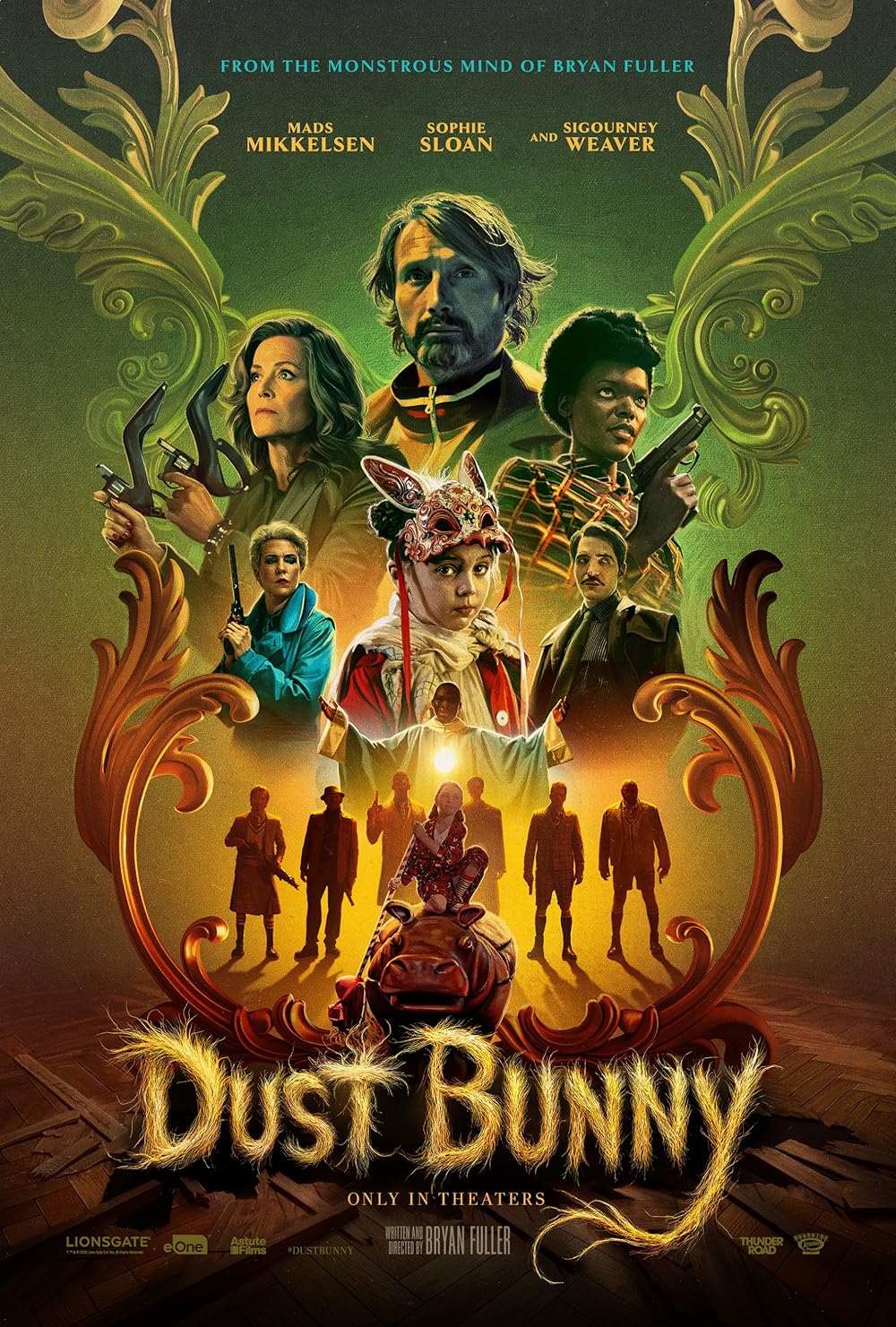

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

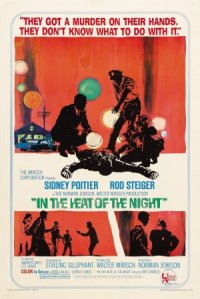

In the Heat of the Night

(1967)

Directed by

Norman Jewison

Review by

Zach Saltz

What we

remember most fondly from

In the

Heat of the Night (1967) is Sidney Poitier’s stirring “They call me

Mr. Tibbs!” parlance, the racist, gum-chewing Chief Gillespie, played in

an Academy-Award winning performance by Rod Steiger, and the modern

recognition of the film being a cornerstone in cinema examining race

relations in America, particularly the south.

What we tend to forget is that the film is primarily a murder

mystery -- an unsuccessful one, with a set-up that’s uninvolving and a

conclusion that is simply outrageous and convoluted.

But I think most viewers can forgive its shortcomings; the true

value of a film, after all, is the sum of the whole of its parts, and

the effect it leaves on its audience.

What I felt most throughout the film was the same bottled-up rage

of the Poitier character -- anger toward an oppressive and archaic

society that stubbornly refuses to accept African-Americans as anything

more than hoodlums and low-achieving hindrances to society.

Unfortunately, the film’s actual storyline mars its effectiveness as a

much-needed social commentary on the sour state of race relations down

south in the 1960s.

It

involves the murder of a wealthy industrialist found dead late one night

on a street in the town of Sparta, Mississippi, and Poitier, a Philly

cop who just so happens to be at the right place at

the right time, is inclined to stay a few extra days to help

idiot racist Police Chief Gillespie (Steiger).

It would be easy enough to pick at the problematic discrepancies

laced in the script, but how much of the actual story of

The Rules of the Game or

Breathless do we really

remember?

It’s more

important to identify the film an important piece of cultural cinema, as

a symbol of the changes that were to come as a result of people’s minds

being opened as they flocked to theaters in 1967 to see it.

That’s not

to say

In the Heat of the Night

is entirely devoid of interest in its story -- the scenes of hot racial

tension are what resonate the best.

The central conflict between the two men is Gillespie’s maligned

assumption that Tibbs believes he’s better than everyone else (which, of

course, he is) and Tibbs’ own astonishment of the ineptitudes of the

police force.

Indeed, there

are three different instances over the course of the film when Gillespie

foolishly arrests an innocent man and charges him with the murder of the

black sympathizer businessman Colbert -- including Tibbs himself, at one

point.

This leads to the

film’s best scene, as a weary and tired Tibbs is arrested while waiting

for his train to return to Philadelphia.

Gillespie’s reaction to the discovery that he has arrested a

fellow officer is almost worth the price of admission alone.

The

technical aspects of the film are noteworthy due to the A-list roster of

names behind the scenes.

Haskell Wexler’s camera works best when it focuses on the magnificent

faces of Poitier and Steiger; we see Tibbs come THIS close to breaking

it at least three times, and Gillespie’s visage expresses a somber

isolation when he gradually accepts the notion that Tibbs is a better

cop than he’ll ever be.

The

upbeat funk score is unmistakably Quincy Jones, and like the soundtrack

of a certain other film released in 1967,

The Graduate, the music adds

a cultural significance that makes the film timeless.

Sidney

Poitier is certainly an American legend onscreen, and appeared in almost

every racially-themed motion picture of the 1950s and 60s:

Blackboard Jungle (1955),

A Raisin in the Sun (1961),

Lilies of the Field

(1963), A

Patch of Blue (1965), and

Guess

Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

He was the Hiram Revels and Jackie Robinson of the cinema -- the

first black actor to get top billing in major motion pictures,

rendering thousands of black actors to find work and inspire a sect of

battered Americans to find strength and solace in their struggle for

equal rights.

And while

Poitier won the Academy Award for

Lilies of the Field, Virgil Tibbs is his most memorable creation; a

brilliant detective as well as a symbol of hope to a ravaged minority of

Americans.

That he refuses

to be referred to as “boy” or “nigger” or even “Virgil” speaks volumes

about even the smallest battles that must be fought -- the struggle to

be recognized as a formal and unencumbered Mister Tibbs.

Rating:

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

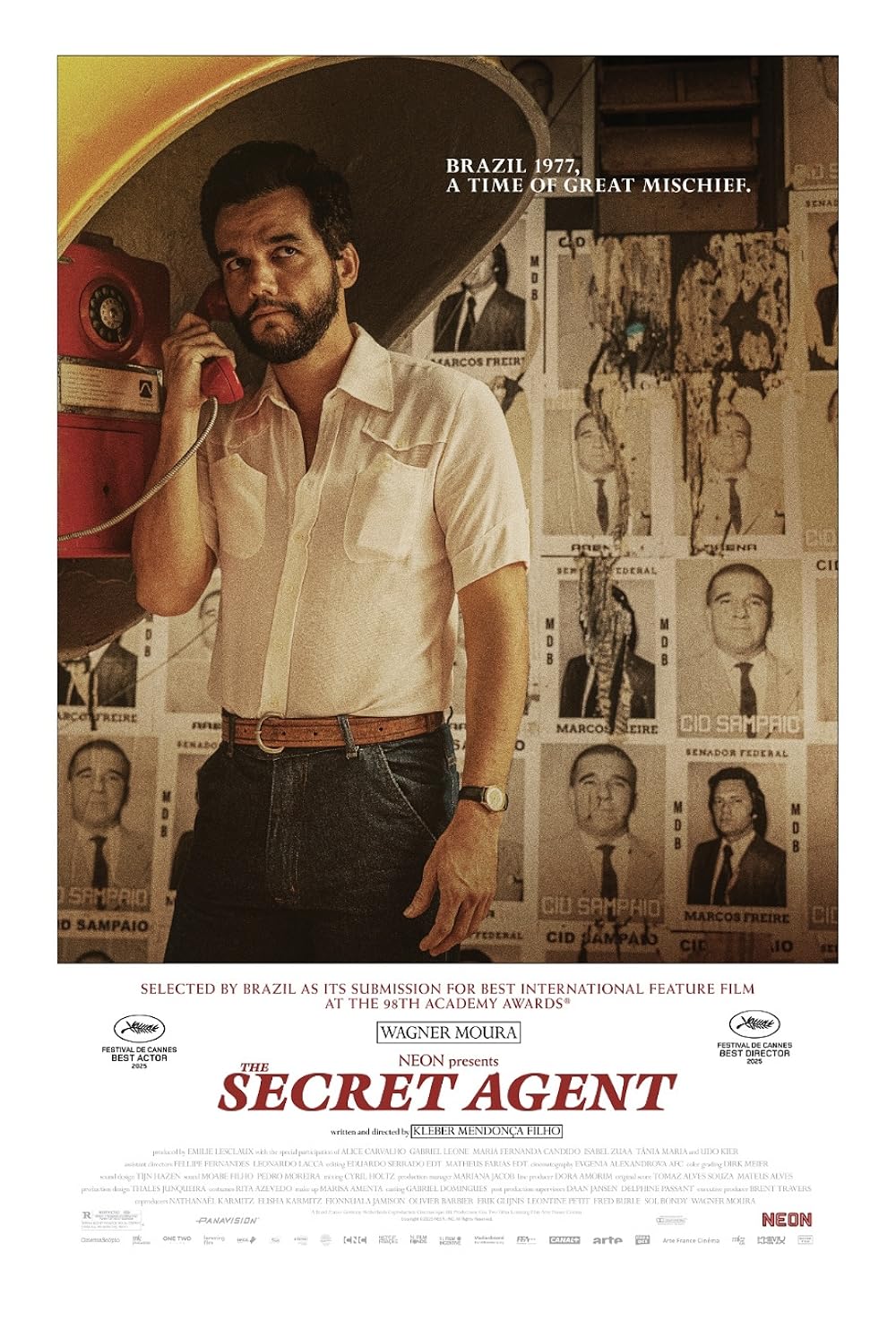

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

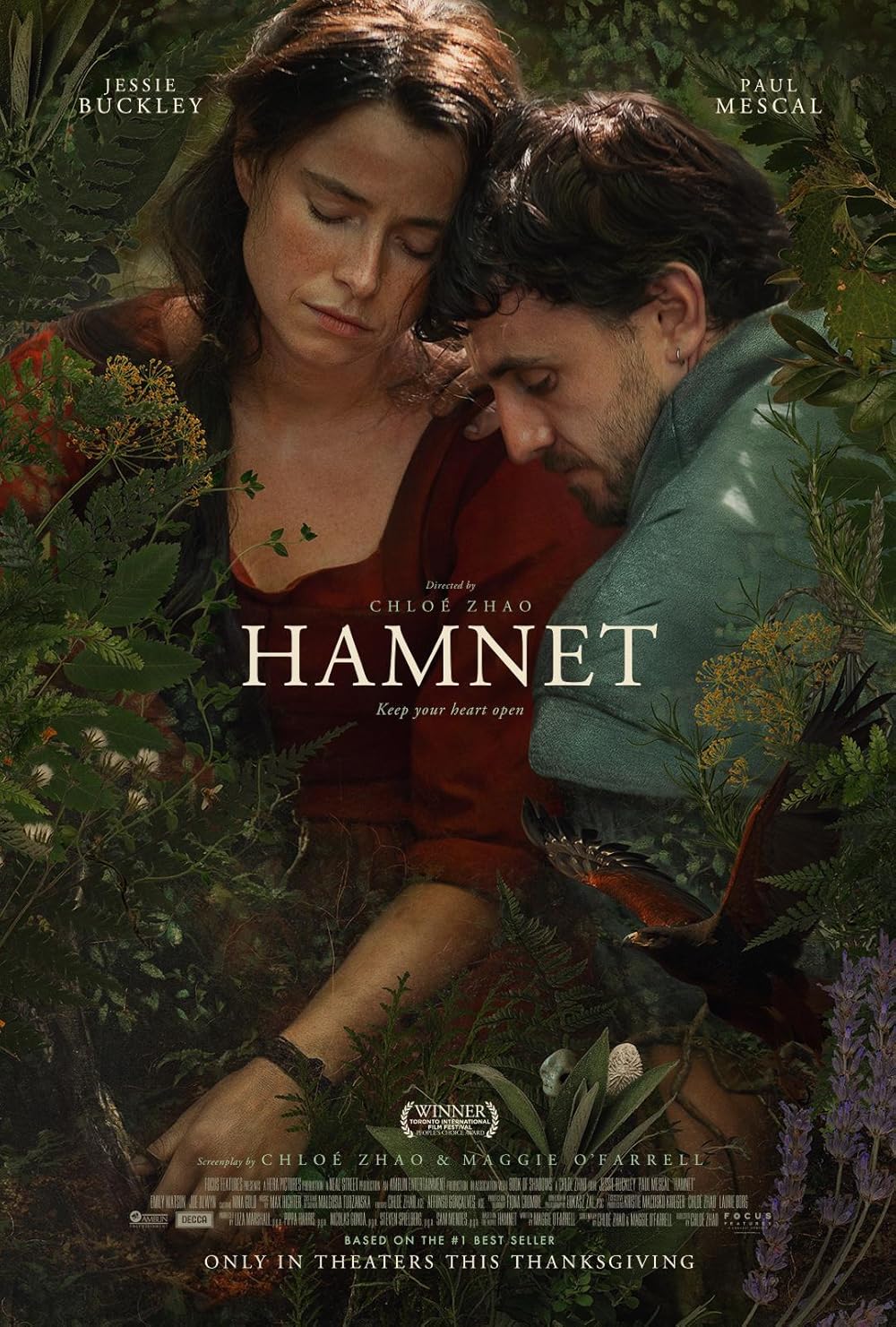

Todd Most Anticipated #5

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

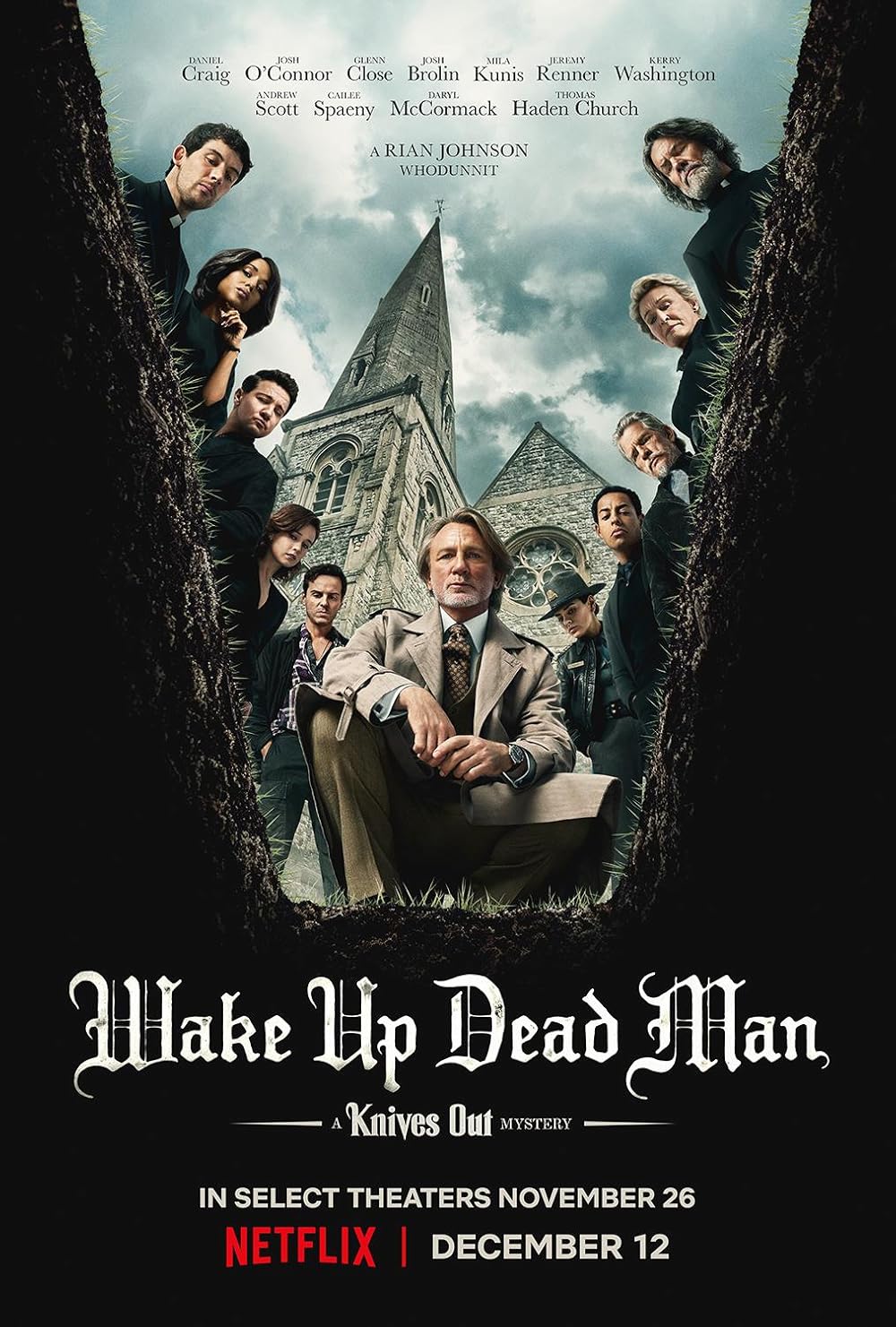

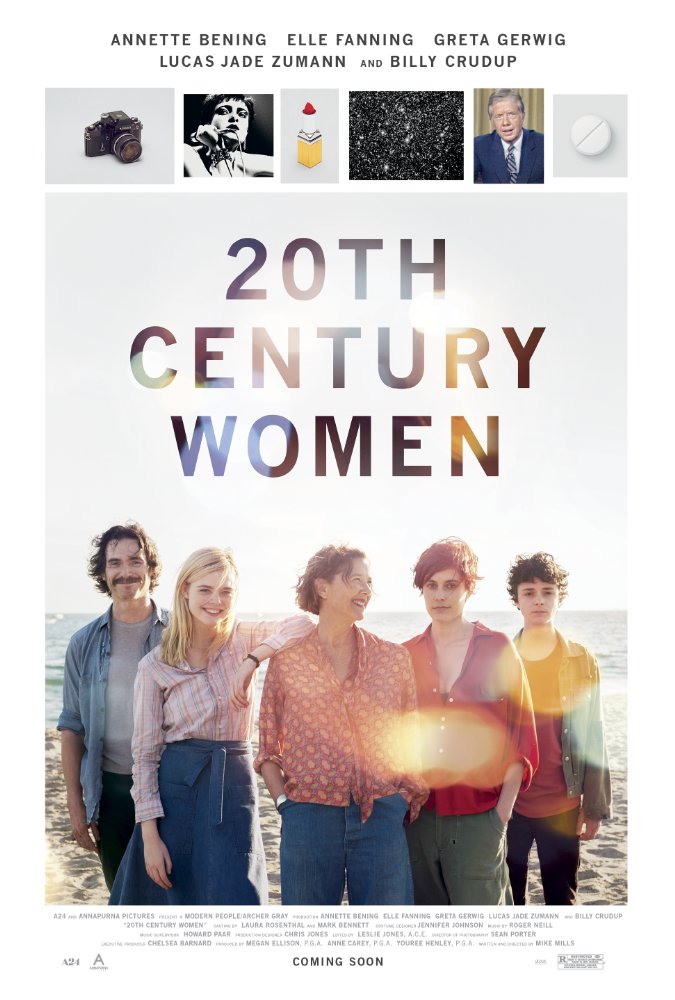

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

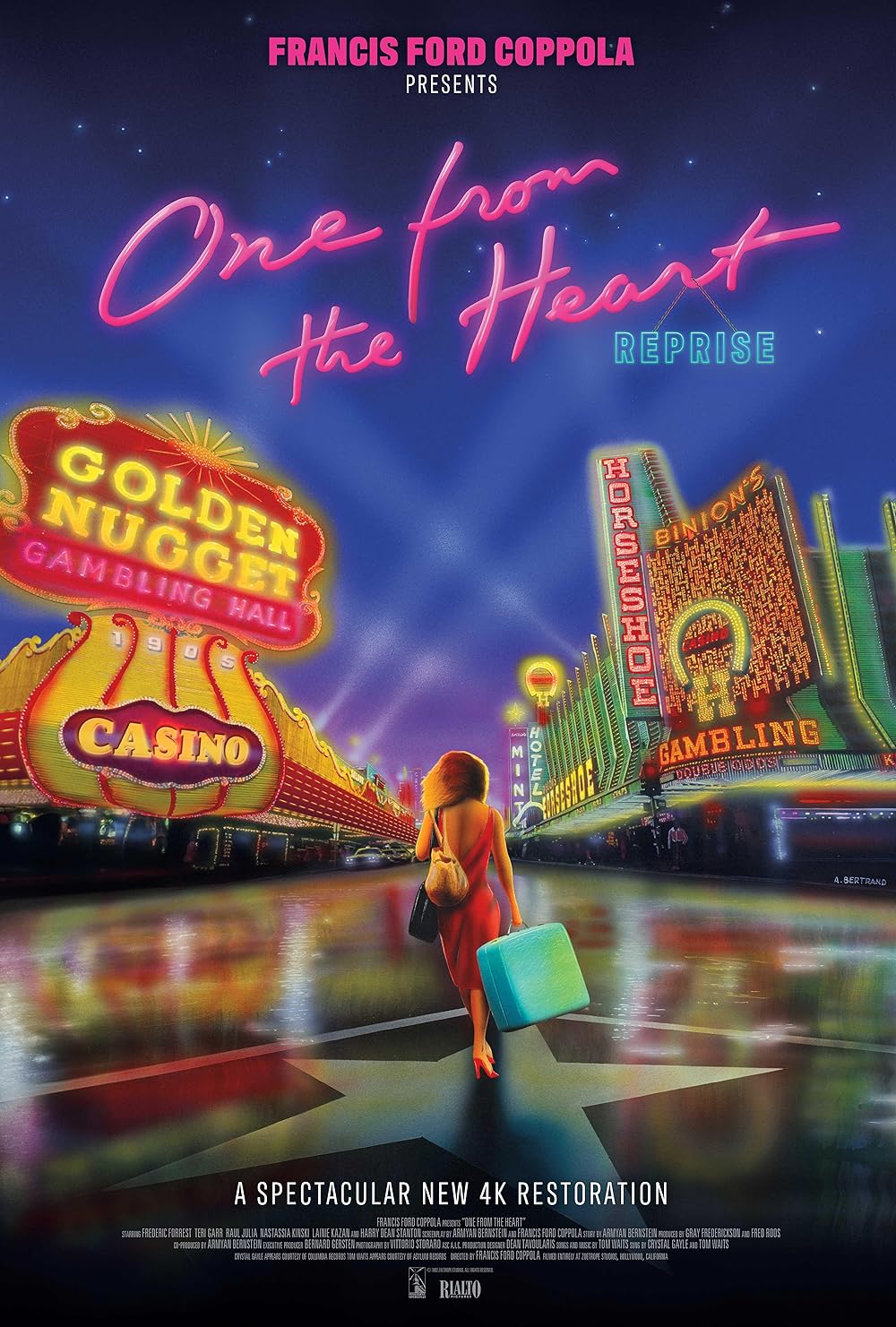

25th Anniversary

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

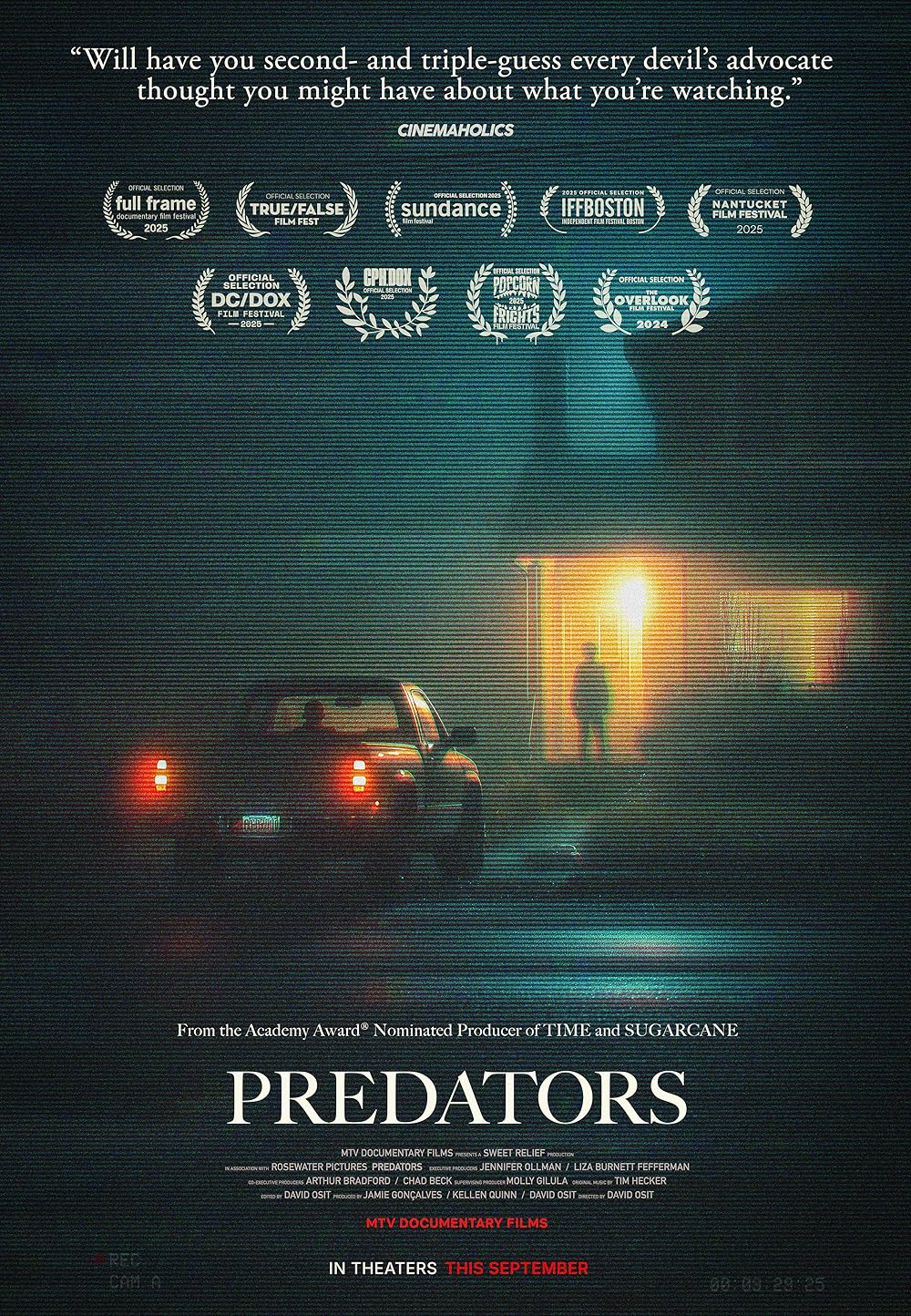

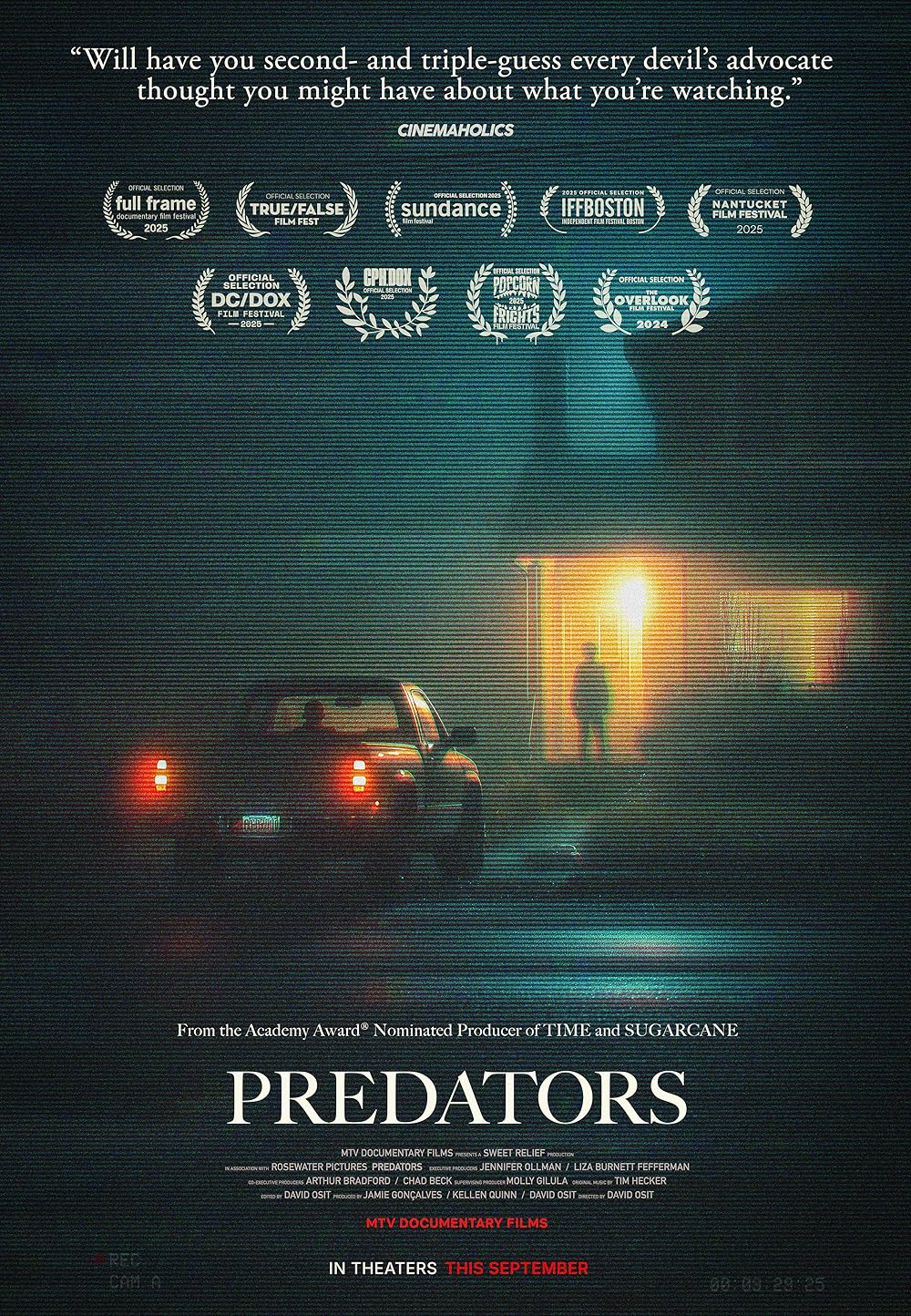

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|