|

New

Releases |

January 16, 2026

|

January 9, 2026

|

January 2, 2026

|

December 26, 2025

|

December 19, 2025

|

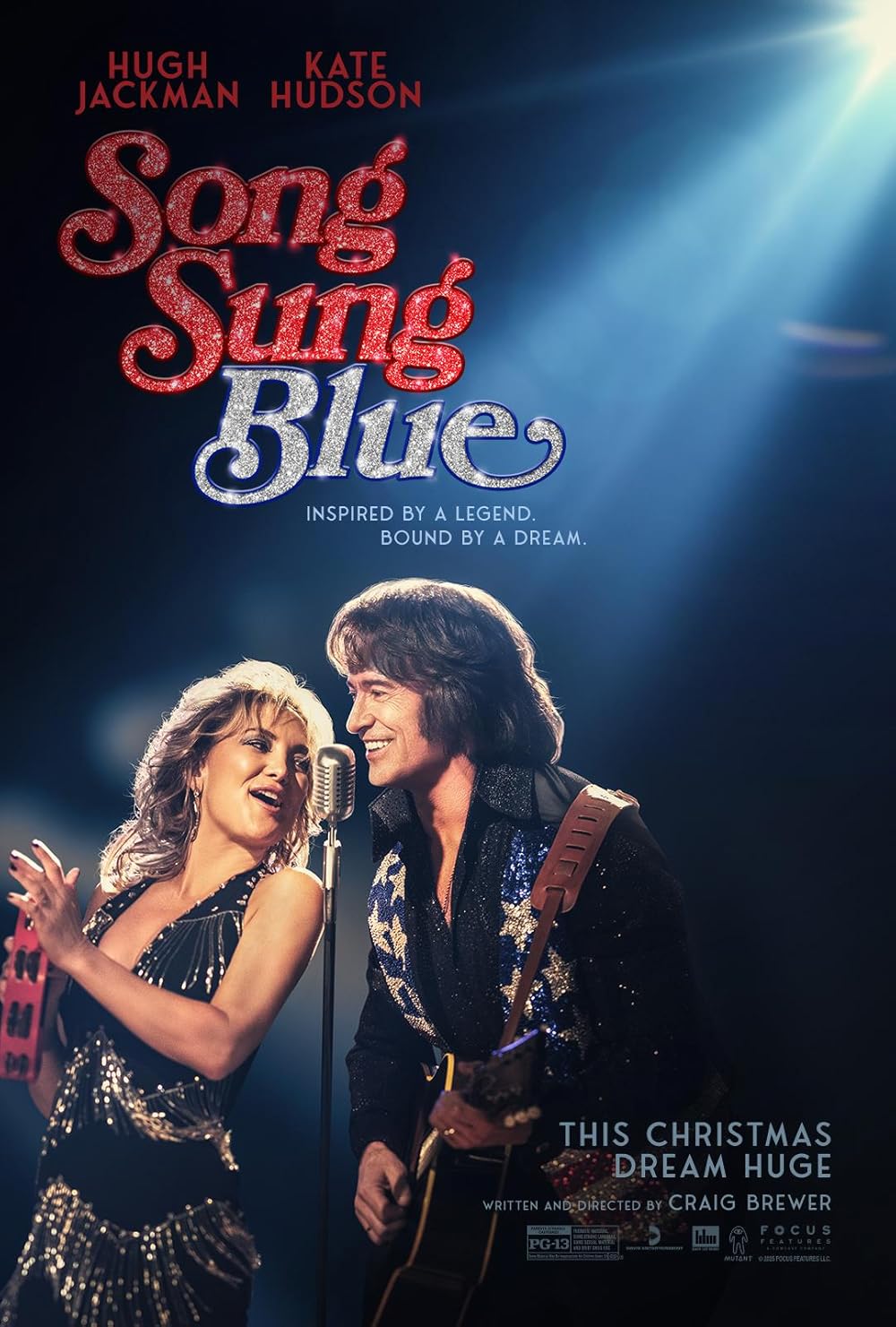

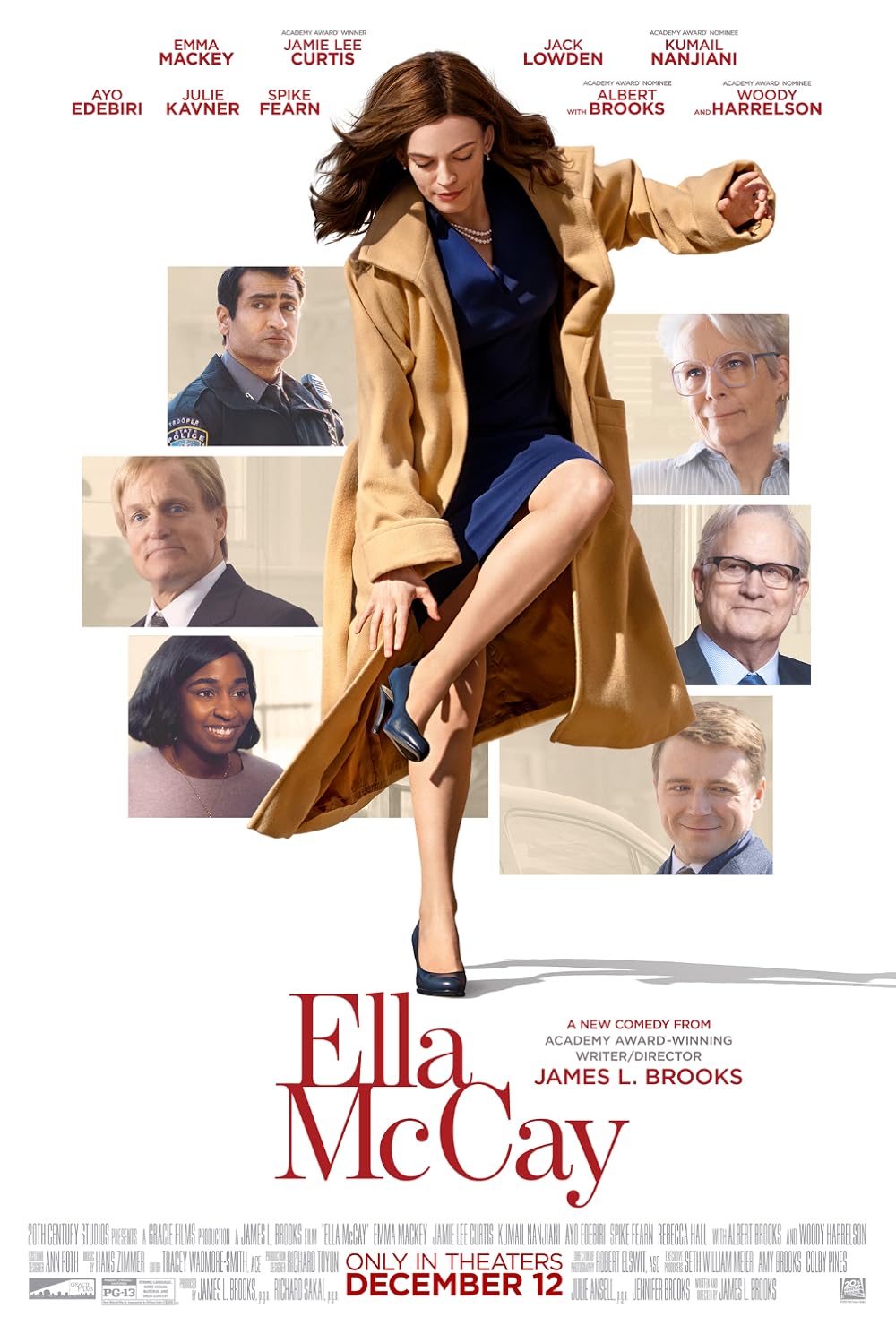

December 12, 2025

|

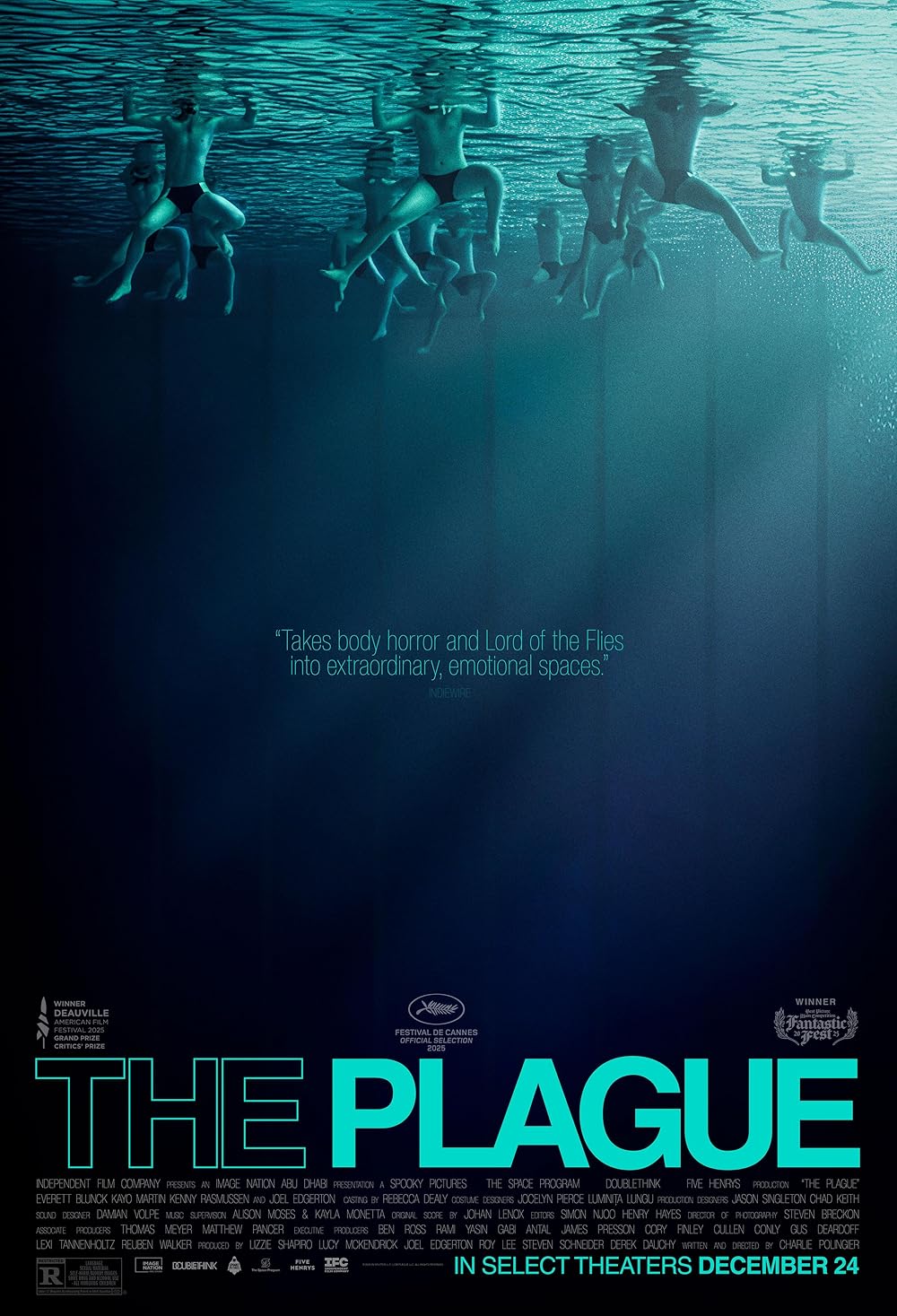

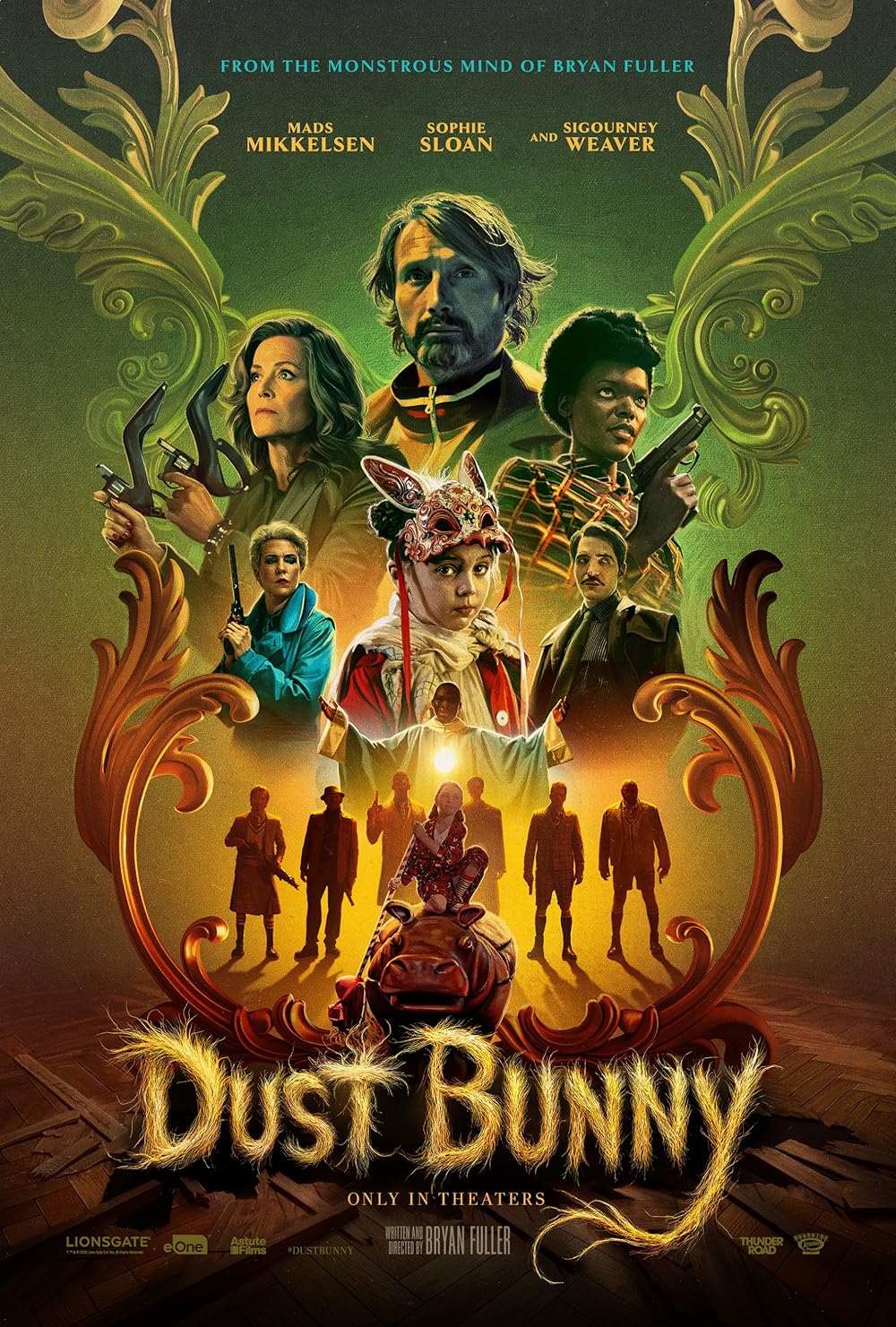

December 5, 2025

|

|

|

|

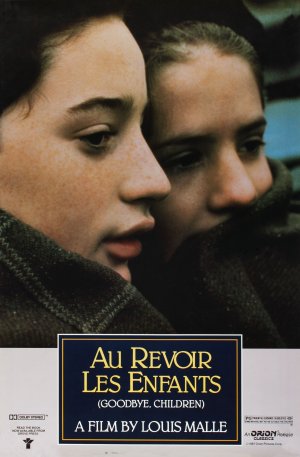

Au Revoir les Enfants

(1987)

Directed by

Louis Malle

Review by

Zach Saltz

Louis Malle’s

Au Revoir les

Enfants (1987) is the retelling of an actual incident in the

director’s life.

It is a

film of supreme suffering and guilt, a testimony to the deep secrets

that lie in us unresolved for the bulk of our lives.

It is a tragedy on two levels -- that an incident of such bleak

sadness should ever occur in the first place, and that it should be

hidden from the rest of the world, its ferocity eating up our conscience

inside.

The film also has moments of such happiness and childhood awe that it’s

a wonder how Malle can pull it off -- offering, in stark, simple scenes,

a film that perhaps says something deeper about the elocution of life

than anything else I’ve ever seen.

By the end of the movie, I could do nothing but stare at the

empty screen in front of me.

The movie has an uncanny ability to haunt and reside inside of you for a

long time after you’ve seen it, just like it most certainly has for

Malle.

It’s unforgettable,

and my Exhibit A when I argue to people how the medium of film can often

be deeply spiritual.

The year is 1944, and 12-year-old Julien Quentin (Gaspard Manesse)

attends a Catholic boarding school in Nazi-occupied France.

The school is run by priests, who are (for perhaps the first time

in movie history) not portrayed as treacherous deviants.

They are loving, trustful men who care a great deal about the

boys and have genuine compassion for the suffering that is occurring

every day as a result of Nazi occupation.

This will prove to be a very important factor in what secret is

revealed at the end of the story.

Julien is a lonely, passive child who does not like school very much.

He is a good student, but finds his classmates immature and

uninteresting.

One day, a

new boy comes to the school.

His name is Jean Bonnet.

At

first Julien is reluctant to make friends with the new child -- “Mess

with me and you’ll be sorry,” he tells him early on -- and since Jean is

more proficient at math and piano, he becomes a natural enemy.

But the two boys soon realize they have more in common than they

initially realize, except for Jean’s mysterious past, which remains

hidden for most of the movie.

But that does not prohibit their friendship in any discernable

way.

They play the piano

together, they read the erotic (and unquestionably forbidden)

1001 Nights

together, and, in

one particularly mesmerizing sequence, they get lost in the forest

together.

This fraternal

bond is shown in dichotomous contrast to the war-ravaged and violent

adult world around them.

But tragically, almost inevitably, something terrible happens.

I will not say exactly in what circumstances it arises, but

ultimately, a single, split-second glance given by Julien at the end of

the film ends up costing the lives of four innocent people.

The burden cannot, of course, be placed on the boy because he is

still an innocent child.

But

in that momentary glance, the boy becomes an adult, but not in a way we

would ever expect or want for ourselves.

The violent adult world has finally dealt its evil and crooked

hand into the idyllic setting of schoolboy life.

Louis Malle was no stranger to controversy, as his films dealt with

everything from incest to child prostitution to expatriates in WWII

France.

He clearly was aware

of this and rather than ignore it, he chose to play tricks on his

audience to exploit their darkest expectations.

Malle employs two tricks on the audience in

Au Revoir les Enfants, both of

which should be familiar to anyone that has seen a few of his earlier

films.

The first trick

occurs when Julien wakes up in the middle of the night, and looks down

his pants in discouragement and shame.

We think this may be the first sign of his puberty, so to speak,

but Malle fools us -- rather than a telltale nocturnal emission, it

turns out that Julien has wet his bed, like a toddler.

This exemplifies how Julien is still an innocuous child at heart,

and, when contrasted with the end of the story, we end up seeing great

(and nonetheless tragic) progression.

A very similar sort of trickery was used in the opening scene of

Malle’s Pretty Baby (1978) when we are given a black screen with a woman

screaming in the background.

We think that they are screams of orgasmic joy, but instead, we are

eventually shown a woman going through the process of excruciating

childbirth.

The second trick is less technical and more laden within the context of

the story.

When Julien’s

mother comes for a visit at Easter, she takes her two sons to a nearby

restaurant, where they witness a Jewish man being harassed by local

authorities.

We assume that

these authorities are the Gestapo, but we are dead wrong -- they are

French officers exercising inordinate powers far beyond the parameters

of acceptable behavior (so far over the line that it takes a German

officer to break it up).

This is a clear homage to Malle’s earlier masterwork

Lacombe, Lucien (1974) about a

French boy who becomes a Nazi in order to exercise extreme power over

those less fortunate (a family of Parisian Jews).

Malle is saying that the adult world is a very confusing,

confounding place where the only thing you can count on is people being

corrupt.

In writing

this, I realize now that I’ve alluded quite a bit to the adult world

being evil and the child world being altruistic and beautiful, a

classical French motif of Rousseauian sensibility.

This is a central concept of so many great French movies about

childhood -- Truffaut’s

400 Blows,

Clement’s

Jeux Interdits, and

even Malle’s earlier work (specifically

La Souffle au Coeur and

Lacombe, Lucien).

The message of American films about childhood is that the growth

of a child into the adult world is vital and always shown as positive.

This is not true in French films, which choose instead to

accentuate the awkward pains of childhood only getting worse in

adulthood (see Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series).

Au Revoir les Enfants

is not about one life, but shows three separate but awfully similar

growths -- those of Julian, the protagonist, Louis Malle, the director,

and perhaps the nation of France as a whole, from the dark

days of World War II.

The

question is whether any of these lives have transcended tragic French

adult prison sentence of banal sadness; we can only hope that they have.

Rating:

# 41 on Top 100

# 1 of 1987

|

|

New

Reviews |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

Todd Most Anticipated #5

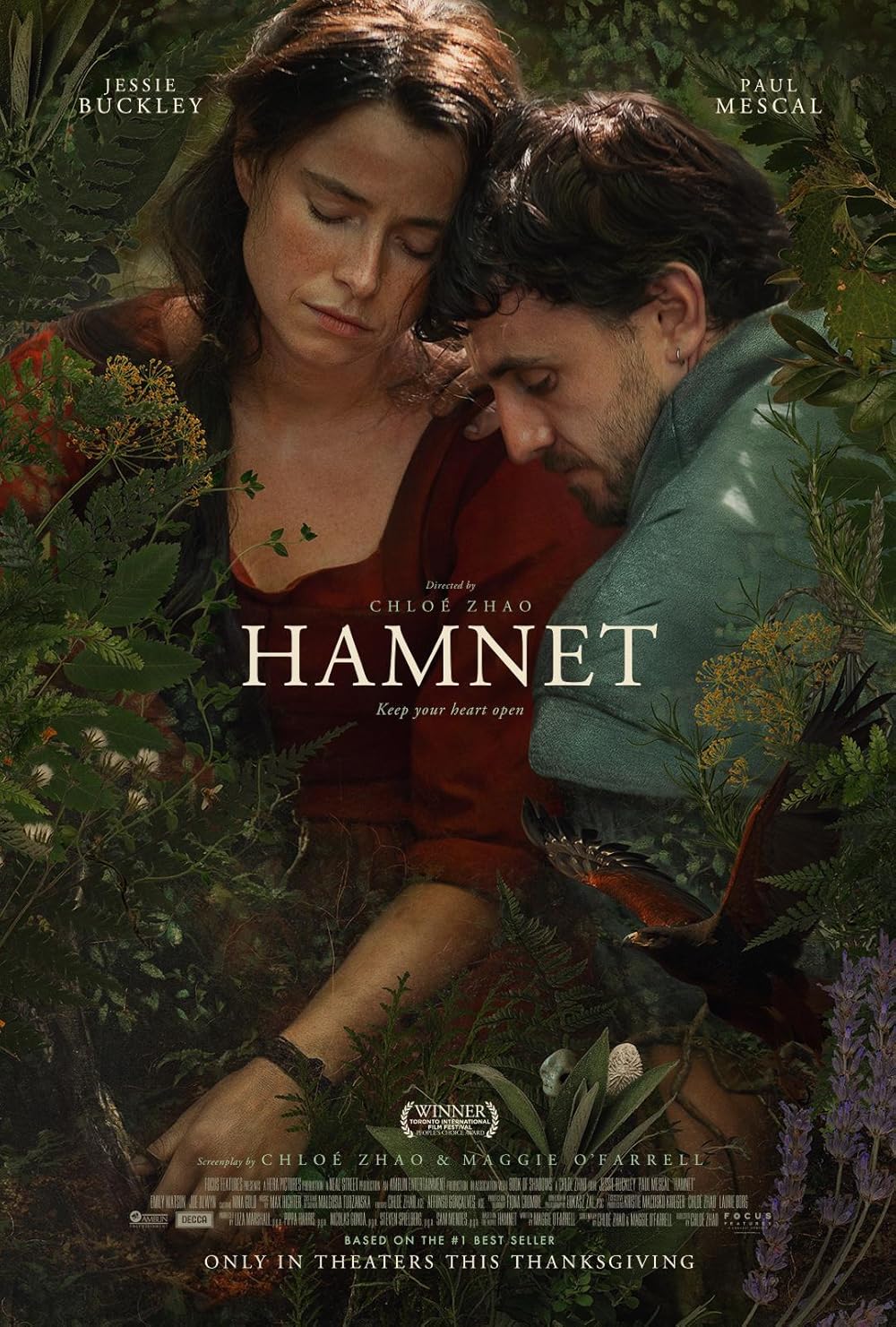

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

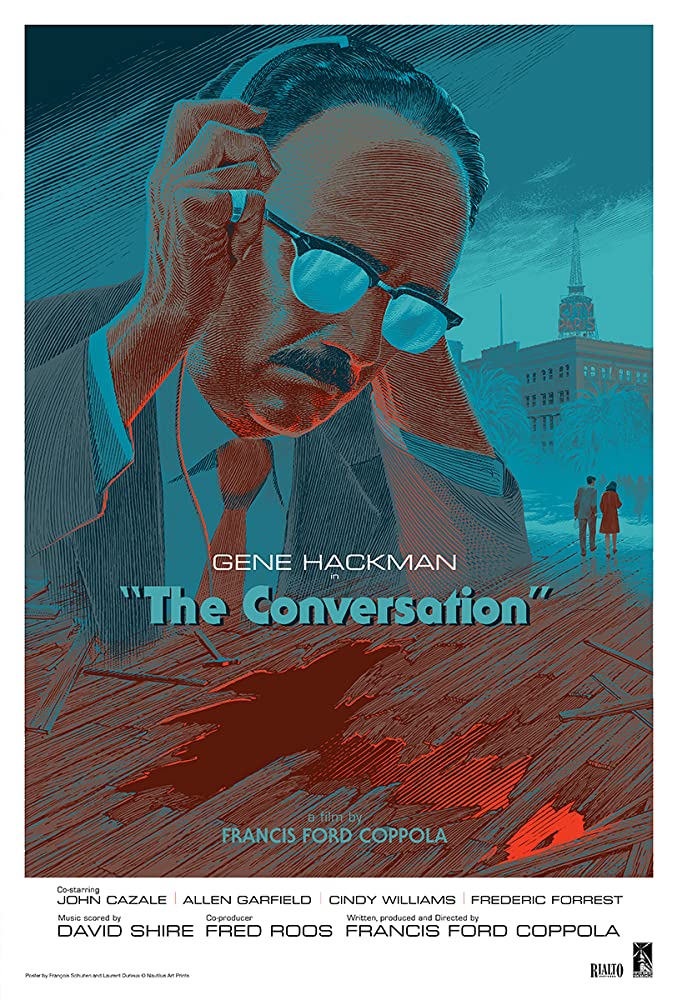

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Director Blindspot Watch

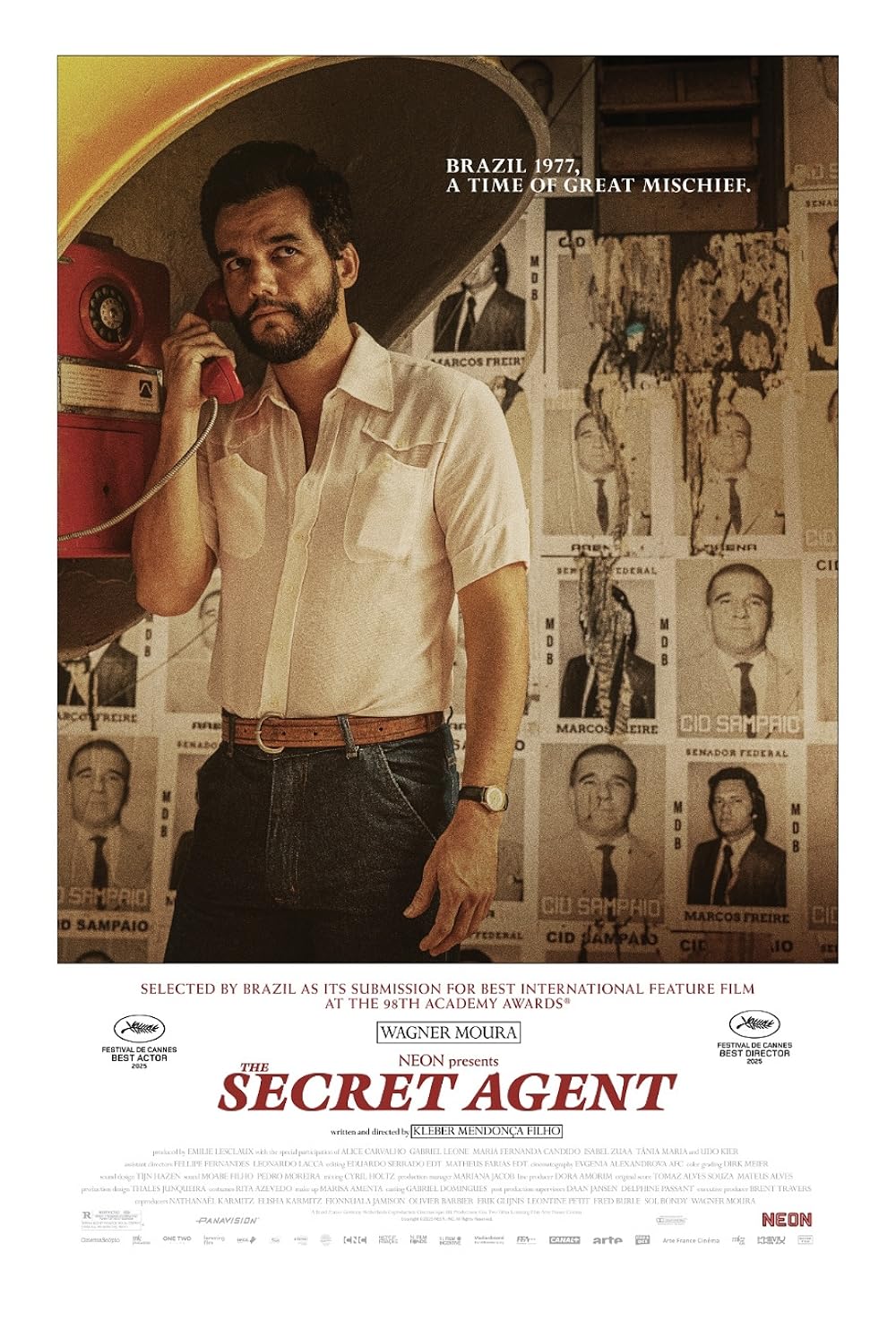

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

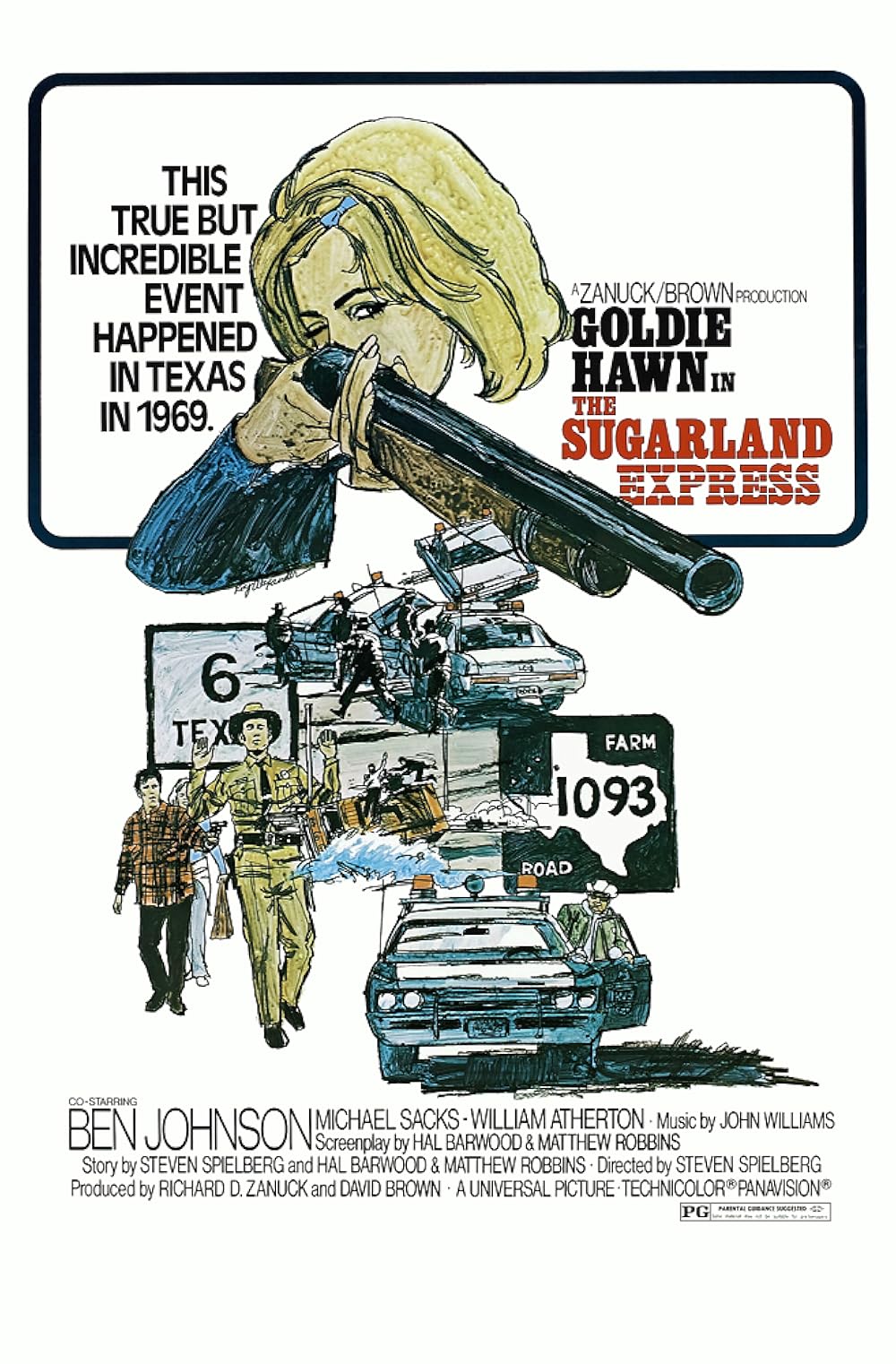

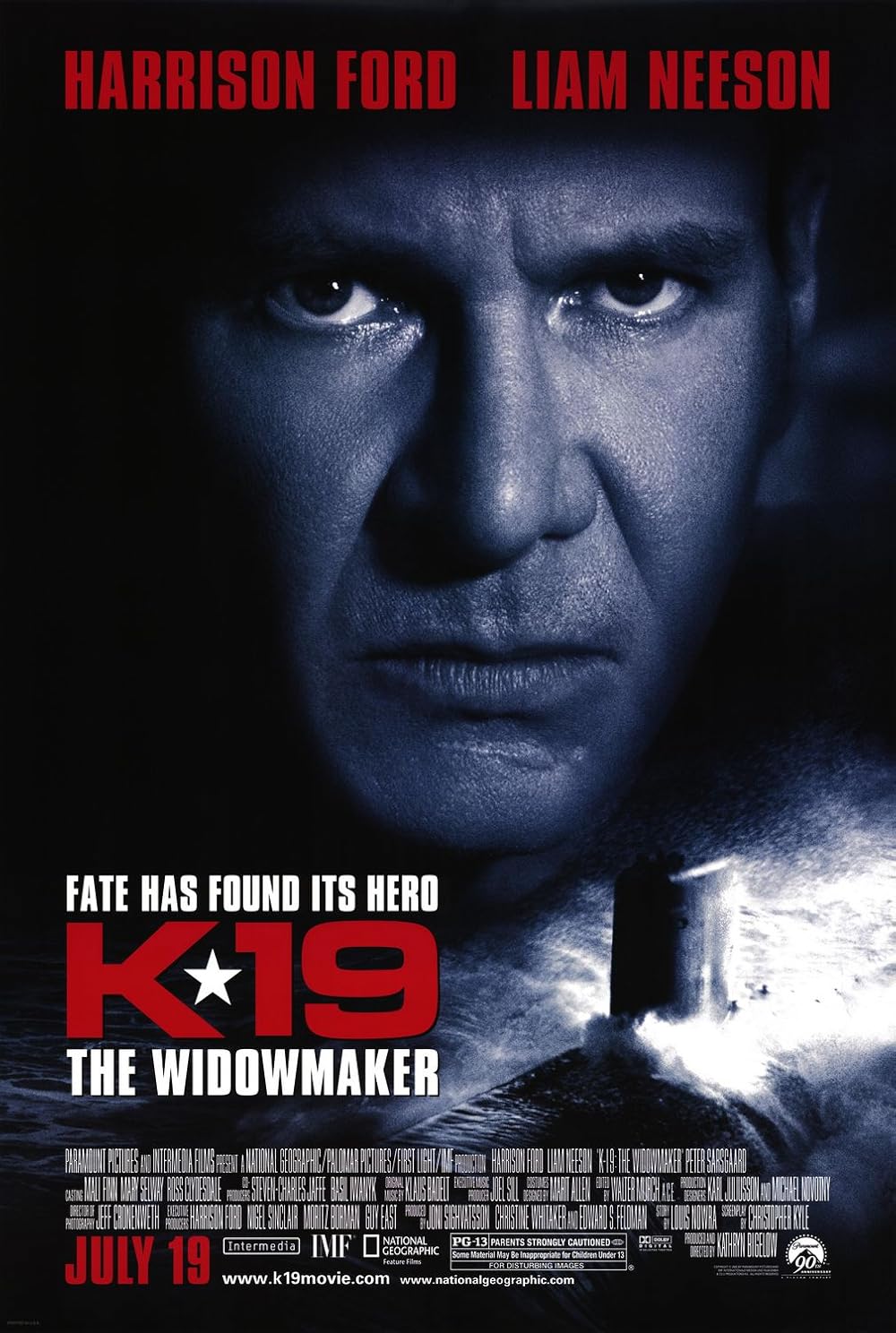

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

2027 Oscar Predictions: Jan.

Written Article - Todd |

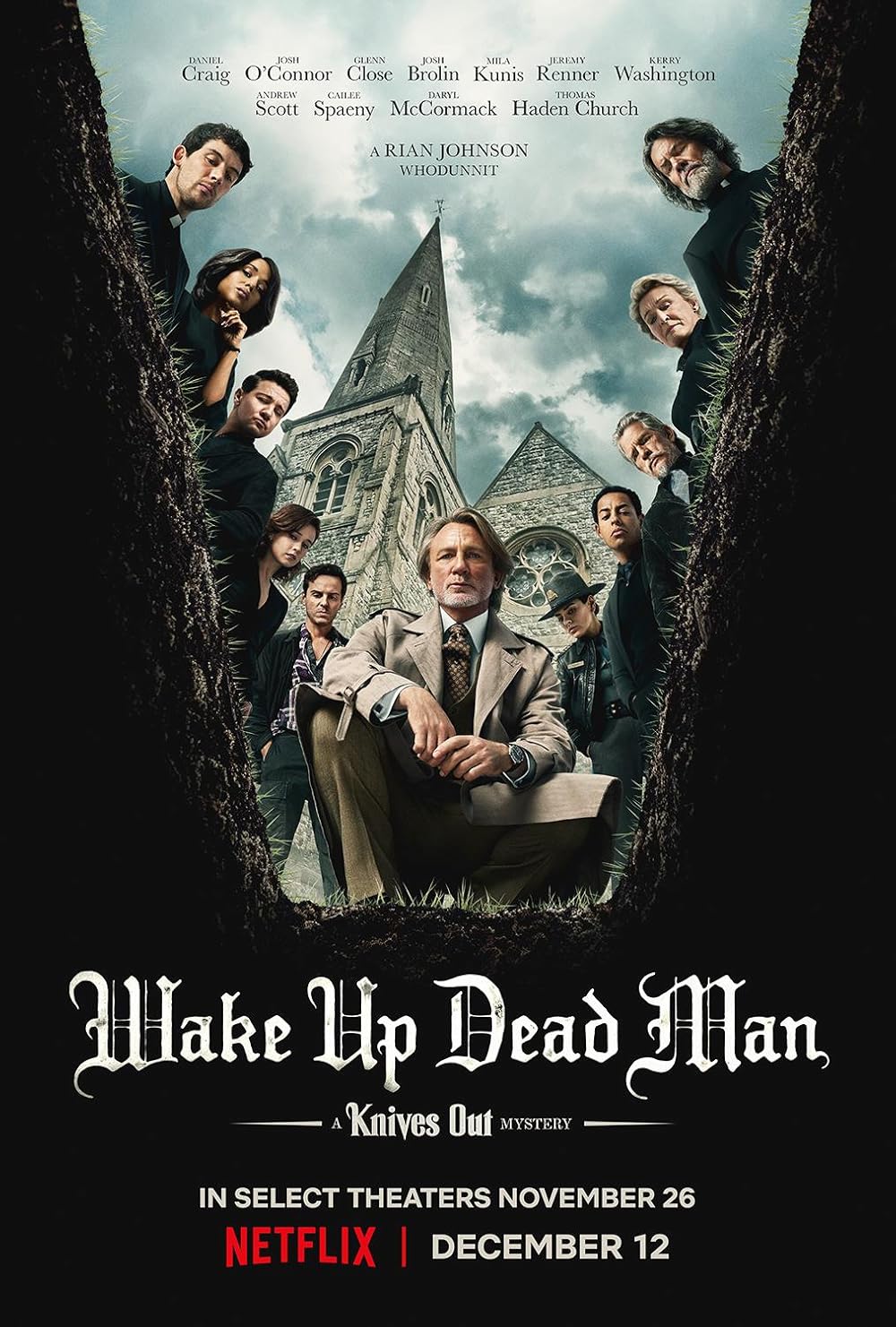

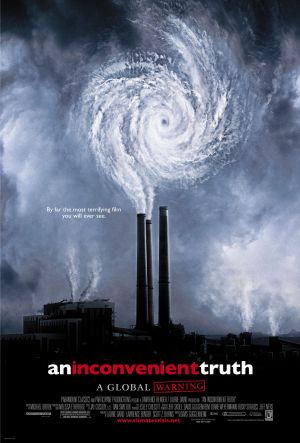

Terry Most Anticipated #2

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

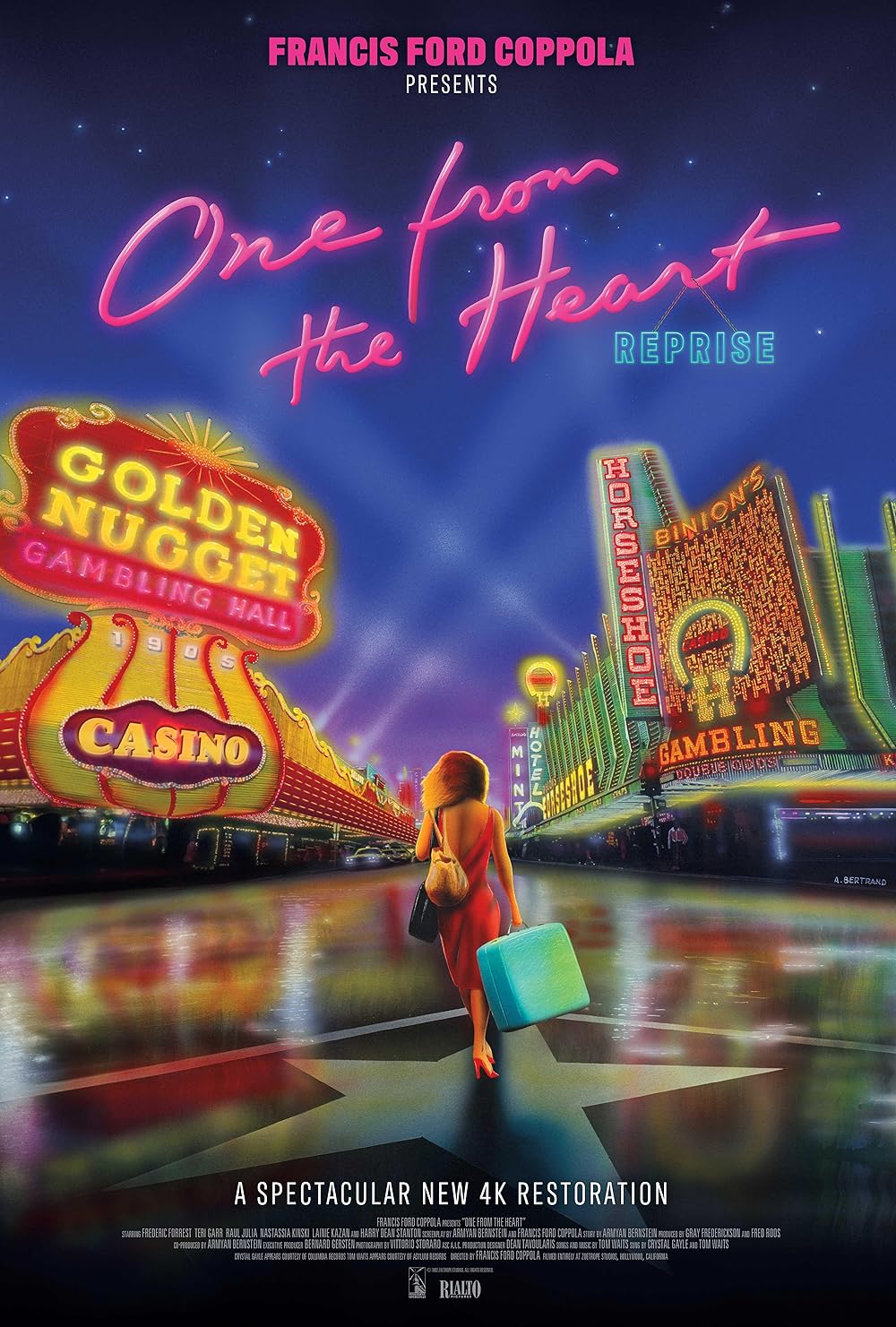

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Ford Explorer Watch

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Trivia Review - Adam |

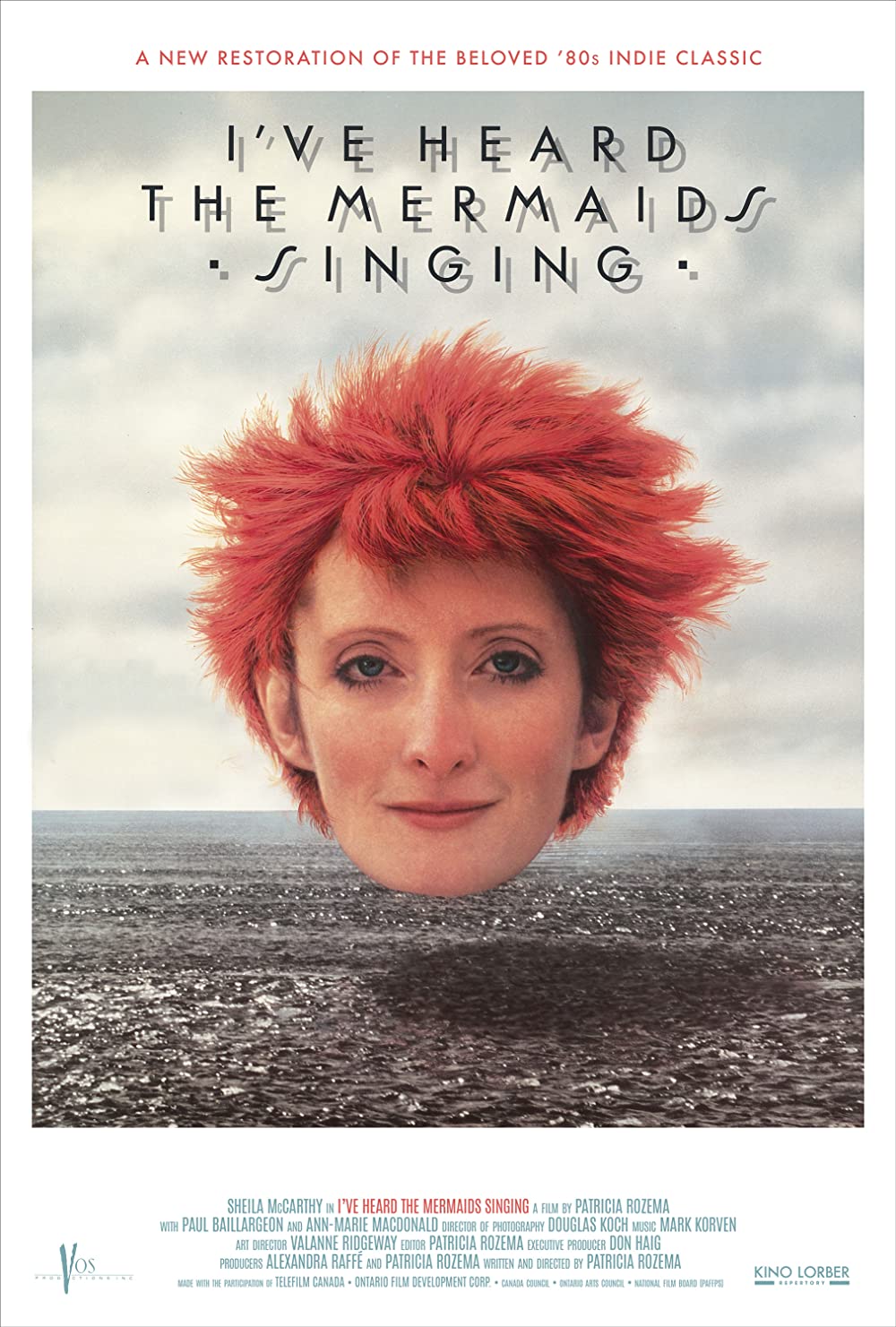

Director Blindspot Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Todd |

Podcast Trivia Review - Terry |

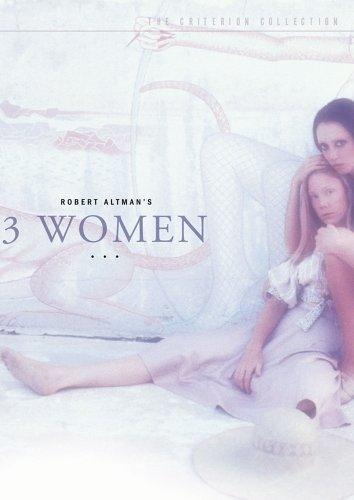

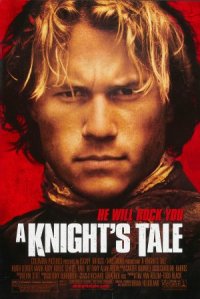

25th Anniversary

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Terry |

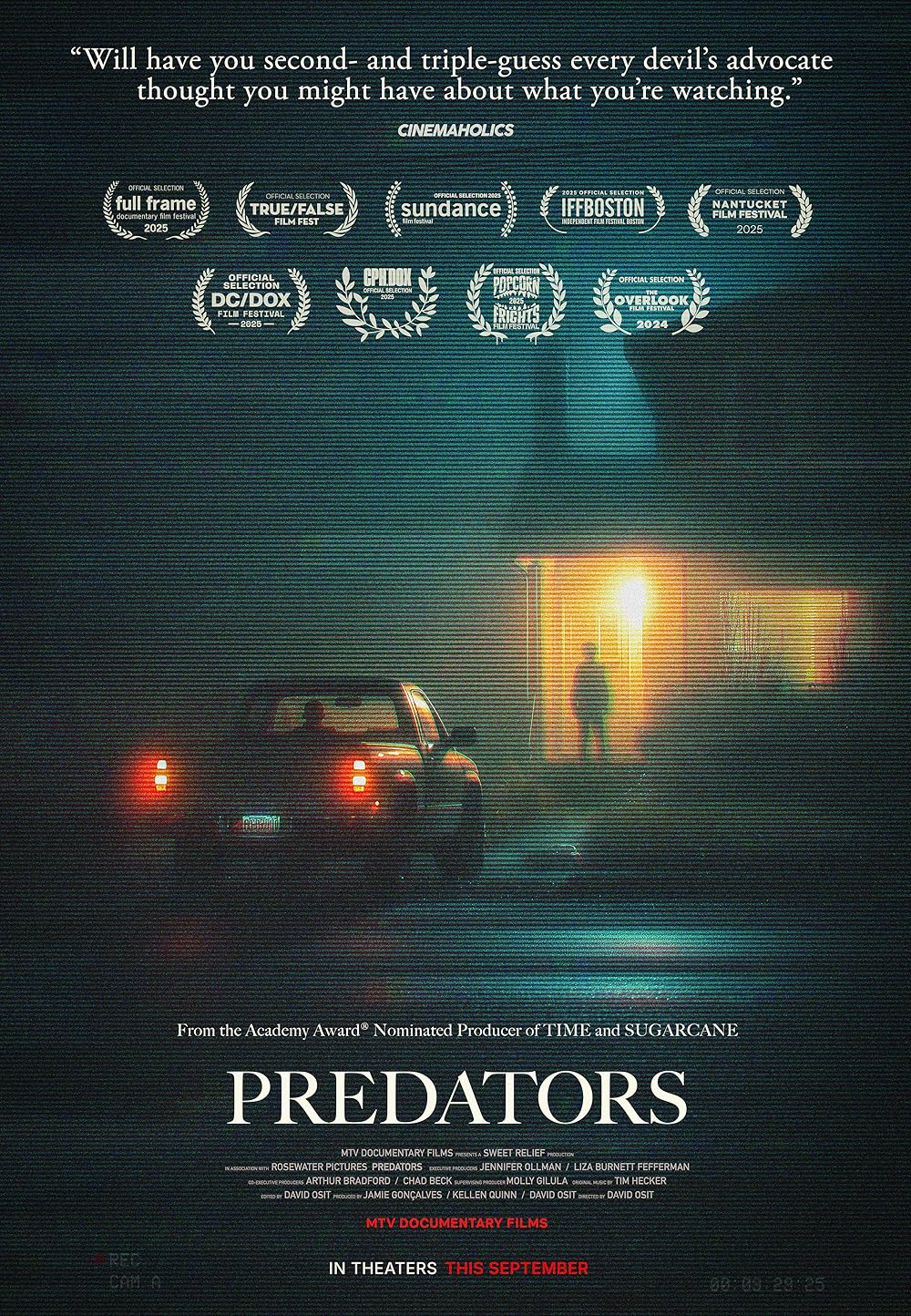

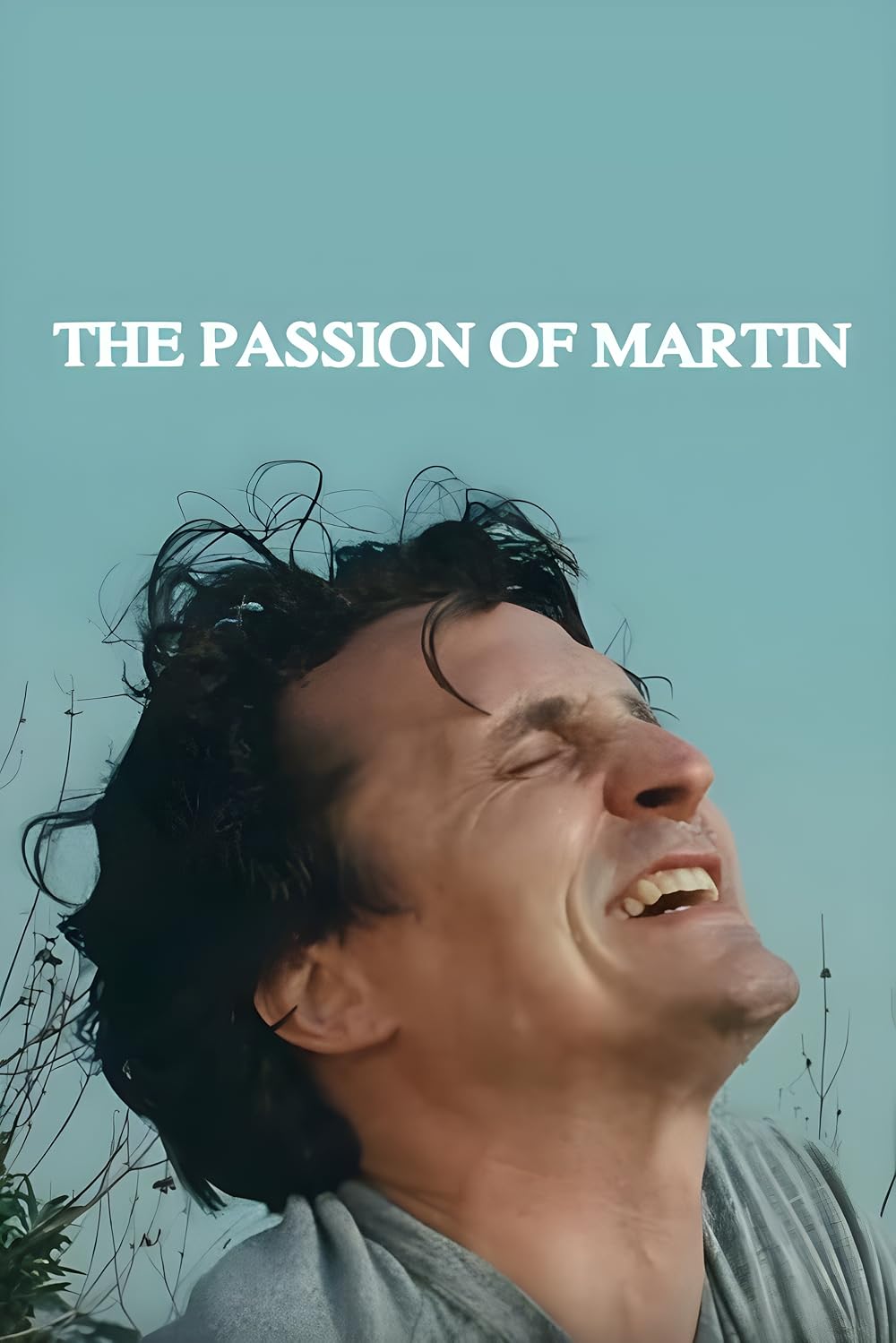

Indie Screener Watch

Podcast Review - Todd |

|

|

|