|

New

Releases |

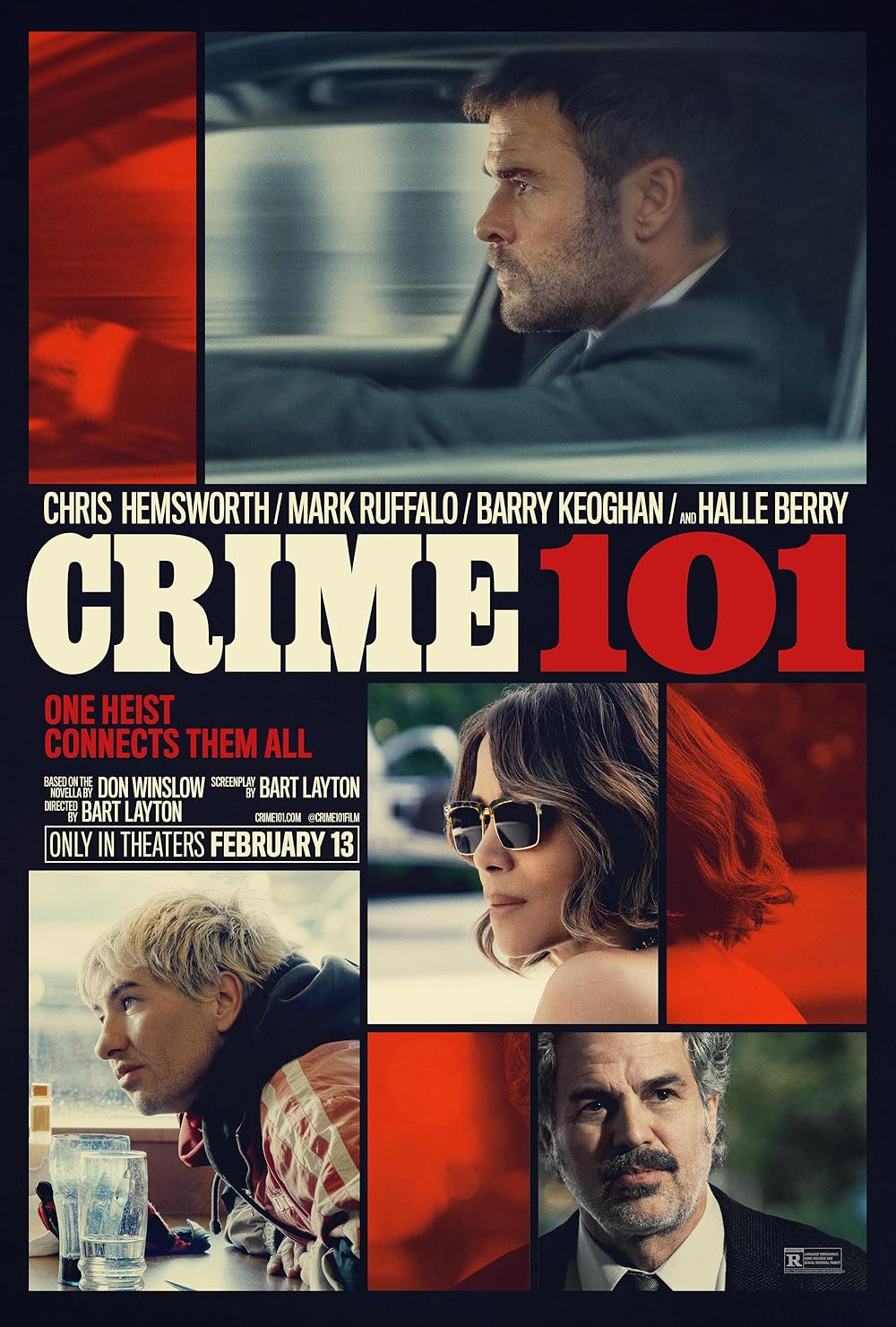

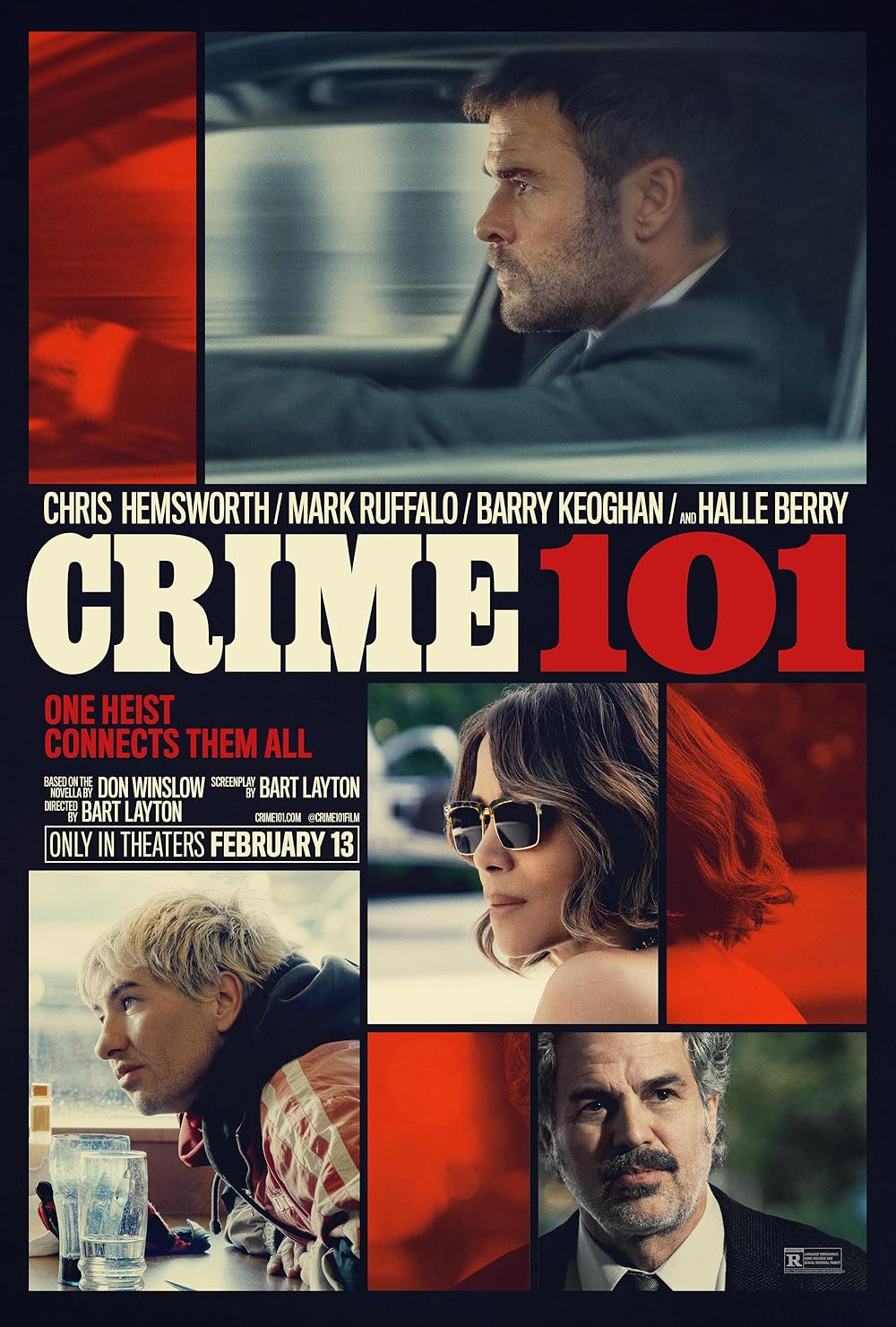

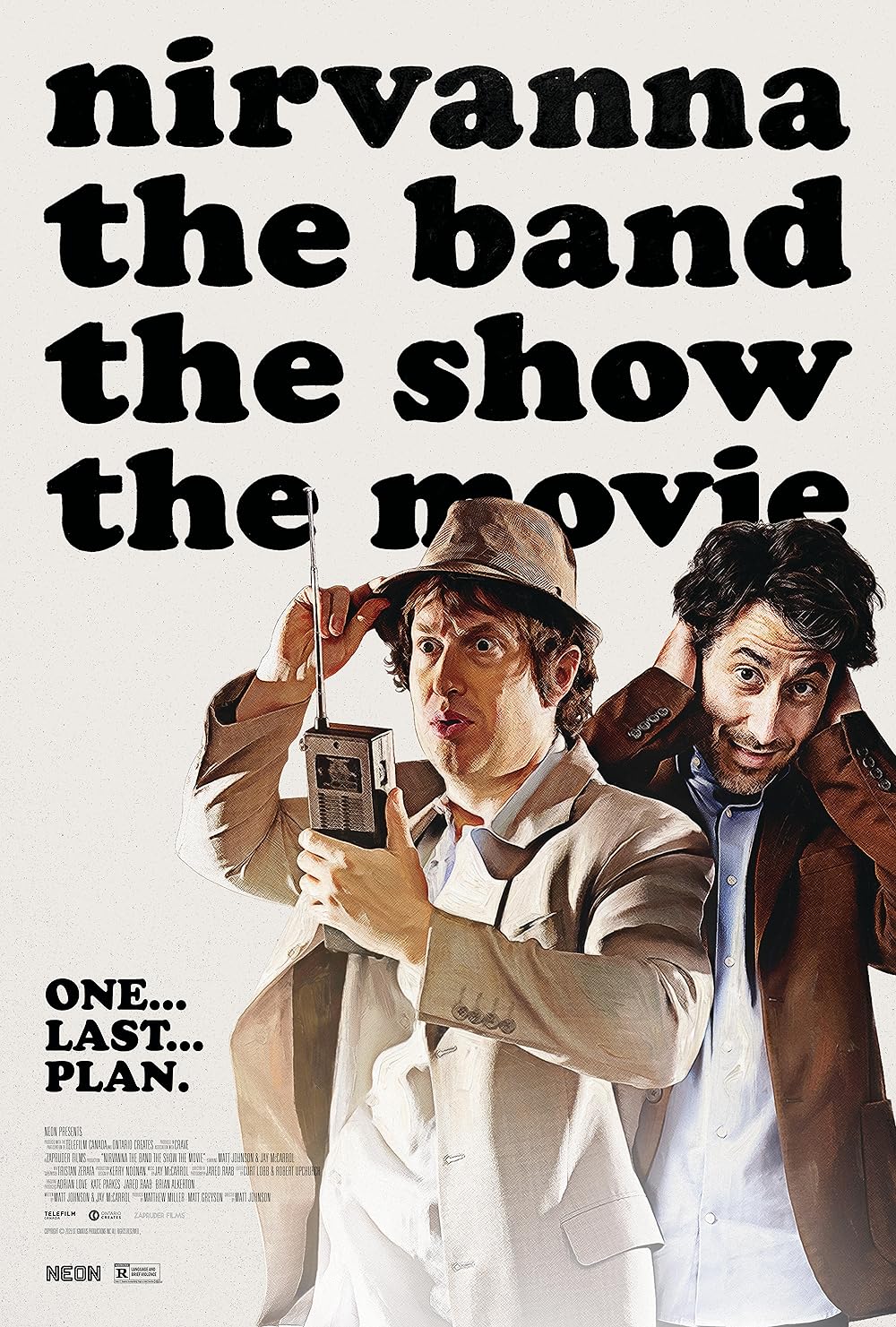

February 13, 2026

|

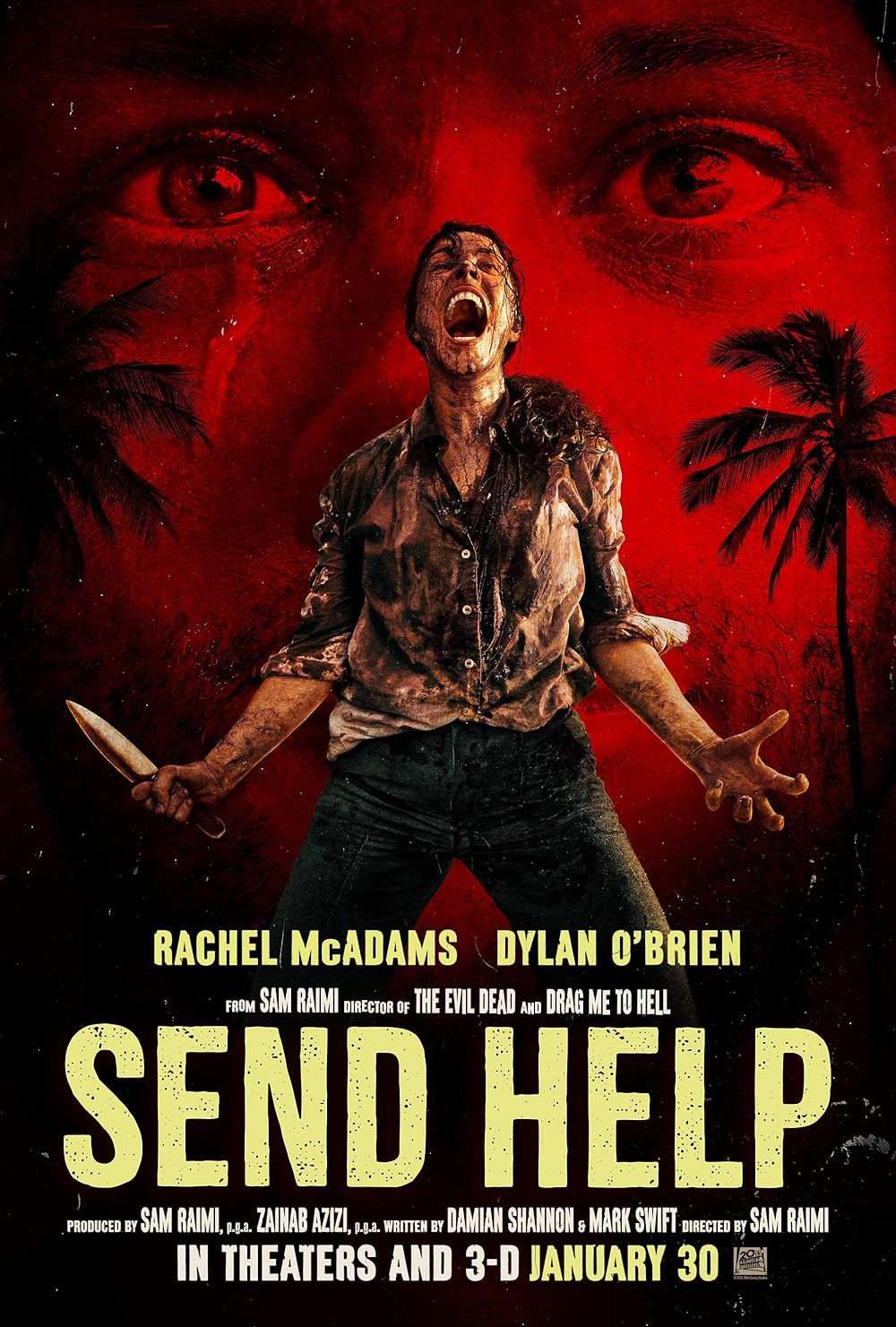

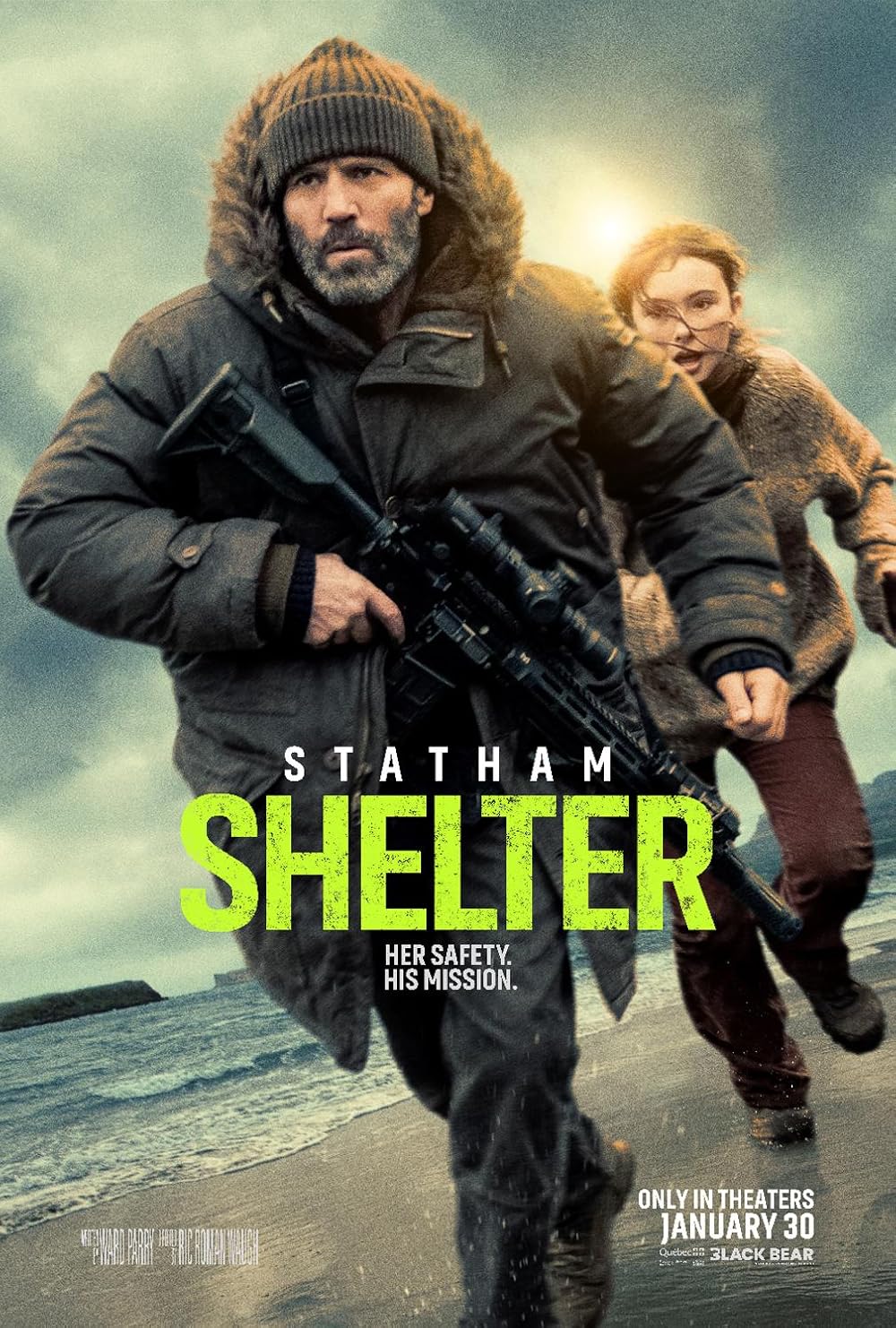

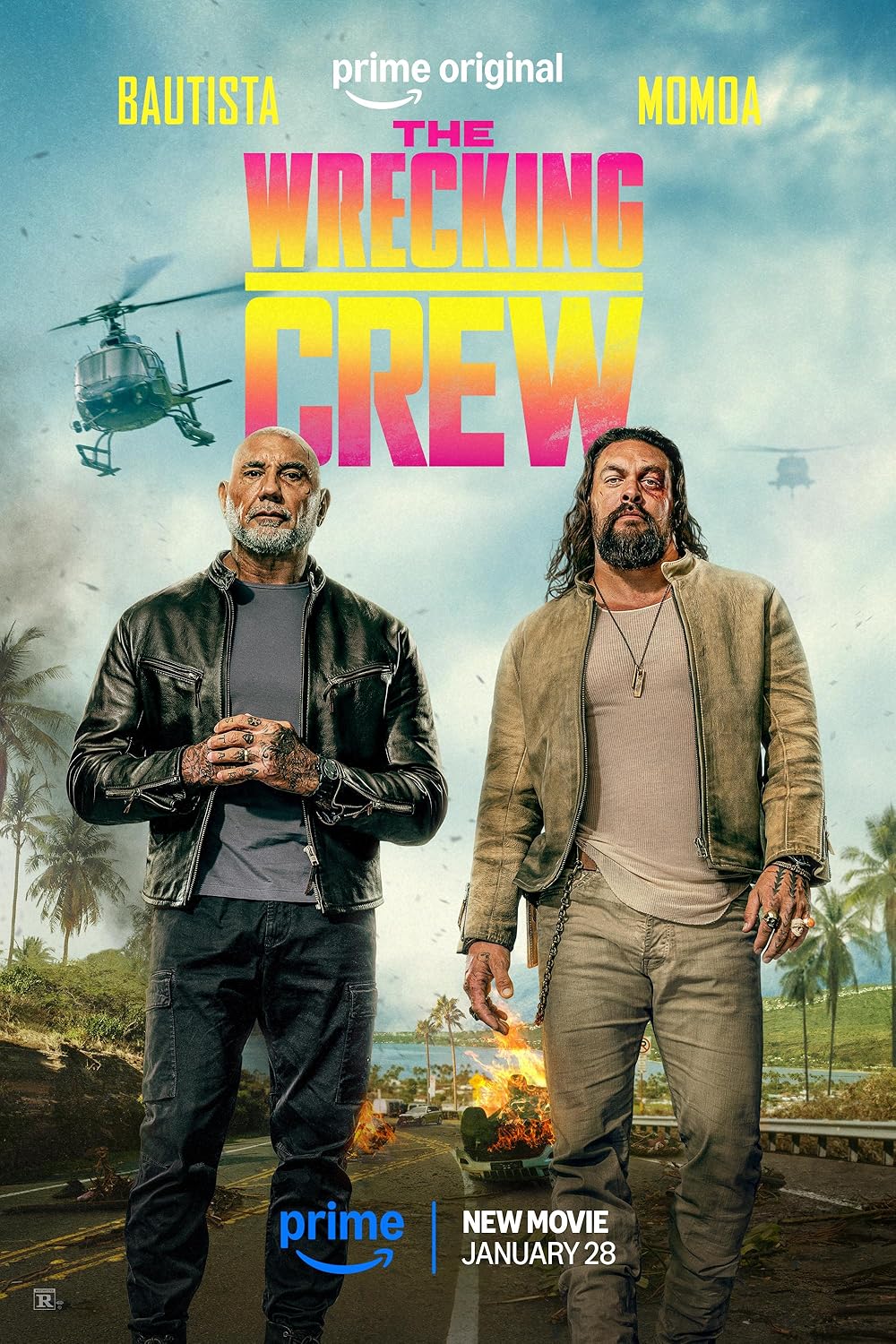

January 30, 2026

|

January 16, 2026

|

January 9, 2026

|

January 2, 2026

|

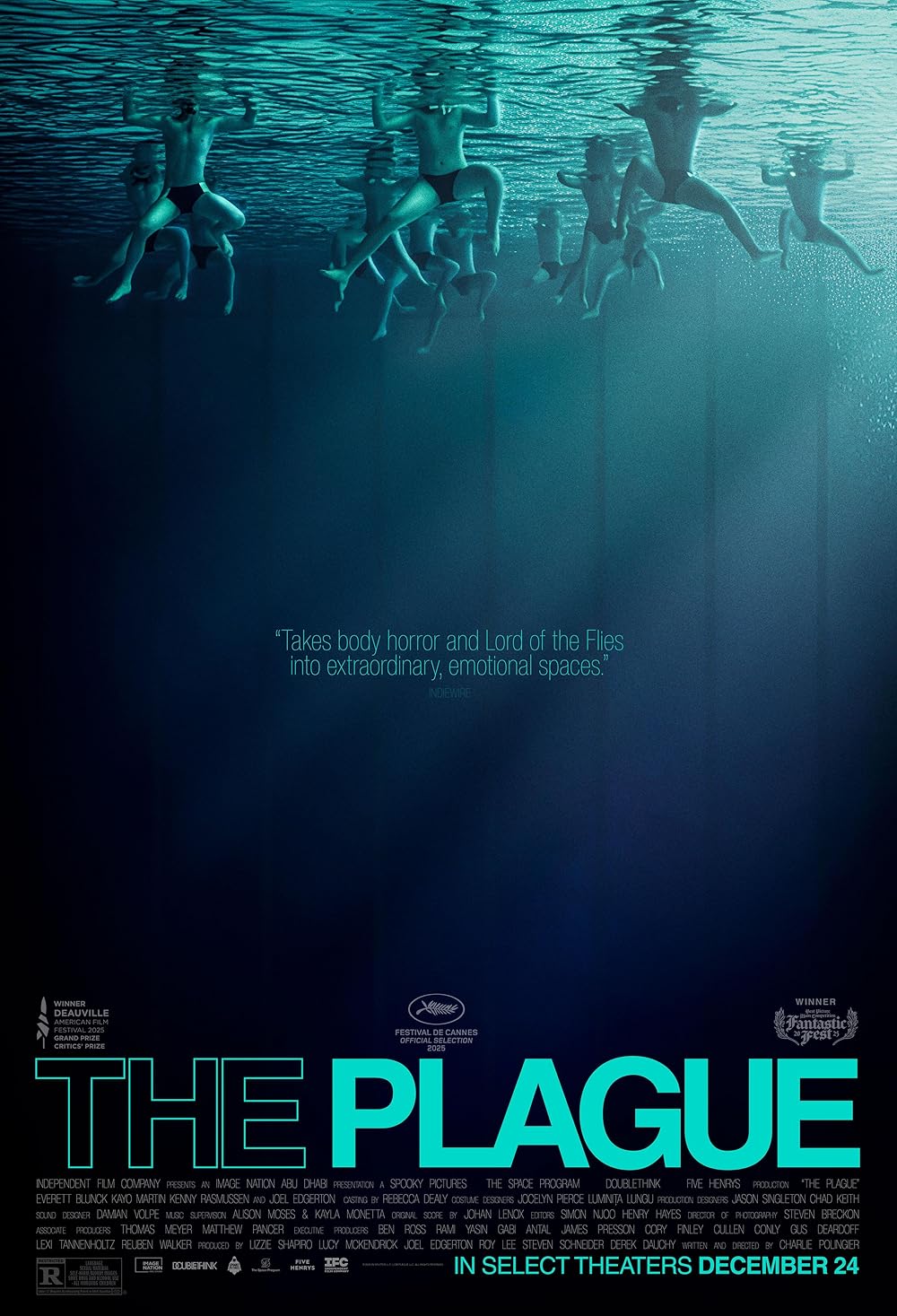

December 26, 2025

|

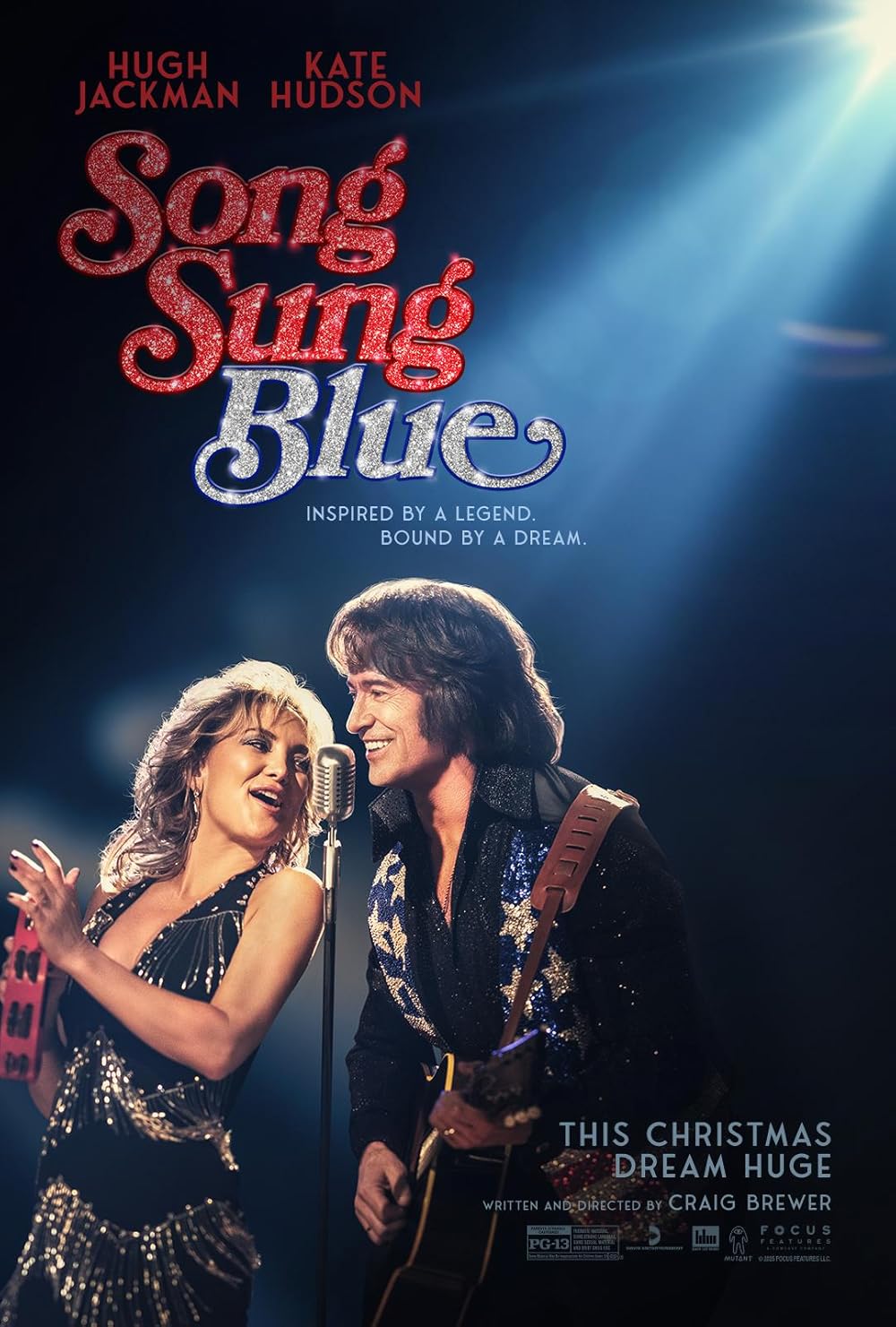

December 19, 2025

|

|

|

|

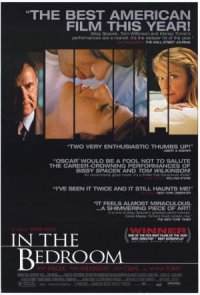

In

the Bedroom

(2001)

Directed by

Todd Field

Review by

Zach Saltz

Posted - 9/20/09

There may be more explosive movies, like

Schindler’s List and

GoodFellas, that are spectacular in

their vision and audacity. There may be more subtle, heartbreaking

movies, such as The Best of Youth and

The Man in the Moon,

whose characters are so well developed that the viewer may feel slighted

at the movie’s finale and at the sudden, solemn realization that these

screen personae will be soon abandoned forever. There may be

movies with great speeches, like The Grey Zone, or movies with

more quirky, naturalistic characters, like

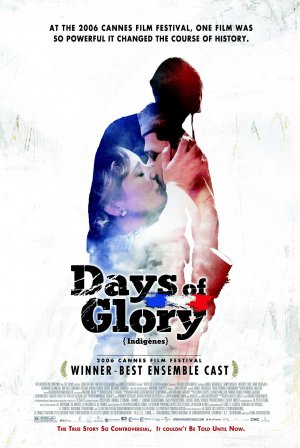

Fargo , or better-shot

movies (Days of Heaven) or more profound movies elucidating the

profundities of the human existence (My Dinner With Andre).

There was once even a movie that brought me to outright tears –

something that has yet to be repeated (Jeux Interdits). But

none of those movies are perfect. Todd Field’s

In the Bedroom

is, and it is in that perfection – that absolute void of a single false

note, a single offbeat or unusual line or framing shot, a single glance

or expression of the characters that could possibly strike the viewer as

untrue – that makes it the best movie I have ever seen.

In the Bedroom. The title is cloyingly

evocative, but not of the sexual nature we might assume. The

meaning and significance of the title is explained in an early scene

(when two male lobsters are put in the same trap as a single female, and

the violence between the creatures which will soon ensue). But

this explanation is plebian, at best. The film is about sex, but

not intercourse. It is about the disconnect between men and women,

and how external events reveal internal truths, leading the male and

female personae closer together. The characters here are trapped in a

vortex of feminine domesticity, and the only way to escape this

claustrophobic milieu is by partaking in male physical aggression.

The façade of happiness rings so often in this film, and it is painful

and inevitable to see it crumble at the hands of the truth slowly coming

out.

In the Bedroom begins in the early days of

summer and ends at the beginning of the impending autumn, and in the

course of that mythical time, the motions of love, grief, and revenge

are examined. These are the film’s three movements, and like a

baroque symphony, each movement has a different texture and atmosphere.

One of the delights of In the Bedroom is how as a result of these

three distinct movements the story is unpredictable and effortlessly

compelling; the viewer simply has no idea what to expect next.

Unlike the Andre Dubus short story from which it is based (entitled

“Killings”), which uses a framework of looking backwards from the

present events – which eventually evolve into the third and final act of

the story – director Field opts to tell the film version in

chronological order, to astonishing effect; quite simply, it is the most

unpredictable film I’ve ever seen. The “looking backwards” effect

may have worked, but Field’s straightforward retelling is relentlessly

compelling: Like many of the great classical symphonies, the film simply

gets better as it goes along, with each new and unexpected venture into

uncharted narrative terrain. So many films begin strong and get weaker

as they go along. This motion picture begins strong, never

falters, and actually gets better as it moves along, until it

reaches its thrilling final climax.

The film stars Nick Stahl as Frank Fowler, an

ambitious college student studying architecture, who is romantically

involved with an older, divorced woman, Natalie (Marisa Tomei) complete

with two children and a resentful ex-husband who wants her back (William

Mapother). The film’s opening scene shows the two lovers

frolicking in a summer field. “I can feel my life, you know,”

observes Natalie prophetically as the two caress each other. This

scene is the epitome of carefree lovers escaping from the turmoil that

will soon encapsulate and ultimately destroy their lives and the lives

of those around them, but there is no indication, from the opening half

hour of the film, that In the Bedroom will in any way be a

tragedy.

The young Fowler character lives with his parents,

Matt and Ruth (Tom Wilkinson and Sissy Spacek). They are both Ivy

League-educated professionals (he is the town physician, she is a high

school choir director) who take pride in their intellect and perhaps

look down slightly at Natalie, who did not complete college and works as

a cashier at a convenience store. They both worry that their son

is getting too involved with her – that “Do you really

think he loves her?” Ruth asks Matt as they lay in their bed one

evening. “Girls always have,” sheepishly replies Matt.

But the merry summer romance is interrupted by the

unwelcome presence of Natalie’s violent ex-husband, Richard Strout

(William Mapother), who refuses to accept that his wife no longer loves

him. An early encounter between the two of them at a kitchen table

reveals the startling dynamics of their relationship; Natalie, timid and

unsure, defines what a good father is, while Richard ruthlessly mocks

and scorns her. Strout then proceeds to provide one of the key ideas of

the film: That his intentions have always remained the same – to protect

his own self-interests – while the circumstances in his life have

changed around him. This notion of individualism vs. external

events will become a central question of the film.

Then, something happens – something of significant

magnitude that should not be divulged in a review of the film. But

it is safe to say that this shattering event changes the entire feel and

purpose of the motion picture. No longer is

In the Bedroom

about the haphazard ways young adults try to break from the grasp of

their overprotective parents, or how Instead, the film

examines the way grief overtakes the lives of characters whose previous

actions could be defined broadly as “good” and “moral.” It deals

with characters trying desperately to preserve normalcy in the wake of

enormous tragedy, and to the extreme measures that it sometimes takes to

ensure it. Like all the great character studies in films, the

second part of In the Bedroom unblinkingly shows the painstaking

attempts of the characters to

The final act of the film again takes an entirely

new direction, this time focusing on the necessary actions done to

rectify the characters’ ennui through the second half. The final

part culminates in an act that few audience members will see coming, not

because the event itself is unforeseeable, but because we don’t believe

the character involved would have the power to indulge in such a

shocking act. The film is not about how external situations altar

our internal urges, but how feminine domesticity and complacency cover

up male aggression, until the rare instance comes along when the

aggression is not only condoned, but warranted by the female ethos.

Like Macbeth,

In the Bedroom

ends with us questioning who

had all the aggression in the first place. Is it that the male ego

has fallen victim to himself, or the female internal anger has impressed

itself upon a hapless man who simply wants to please her? What are

the true intentions of the characters by the end of this picture?

If you have not seen this film, such questions sound vague. But by

the end of this picture, it will be impossible

not to debate its

polarizing and fiercely divisive turn of events.

The acting in

In the Bedroom is, simply put,

the best ensemble acting one is likely to find in a motion picture.

Nick Stahl plays young Frank as innocent, but not naïve; someone who

wants complete autonomy without completely realizing the ramifications

of it. William Mapother is ominous and lucid, but in a painful

scene toward the end of the film that involves a framed picture (rarely

has a film used motifs and symbolism so well), we see the faintest bit

of humanity in this supremely flawed man. Sissy Spacek towers

through the second portion of the film, and many scenes are focused

purely on her grief. She quietly tries to return to her daily

routine, but the breadth of the tragedy is too much to overcome.

There is a stunning scene where the characters around her laugh, and the

camera focuses on her discomfort with humor at the time of grief.

Should she be blamed for her inability to get over the tragedy?

Perhaps she feels more responsible than she leads on.

Marisa Tomei, in perhaps the film’s most difficult

role, brings sympathetic vulnerability yet equally pathetic naivety to

Natalie. Her character is polarizing (right down specifically to

the gender lines of the viewer – men seem to pity her, women tend to

despise her). Either she is too stupid to realize that her

relationship is jeopardizing the well-being of her and her children, or

she is so self-centered that she is willing to compromise all of Frank’s

hopes and dreams. And yet, we sympathize with her because Frank is

the first man in her life who seems to give her any sort of respect.

She is a good woman whose frustrations cannot be realized because of her

social standing with the Fowlers.

But the film belongs to Wilkinson, a Brit whose

solemn eyes and wary posture suggest the veneer of a hard-working,

middle-aged man no longer content with the successes of his own life,

but who would rather get personal fulfillment from witnessing the

successes of his son. An early scene reveals this when he takes an

early lunch break to go down to the pier to see Frank’s catch for the

day. He is more interested in lobsters than surgery, and

middle-age banality has taken a toll on him. Does he vicariously

live through Frank, as Ruth accuses him of? Does he have a choice?

When the dreams and hopes of children are either achieved or lost, than

the hopes of their parents die with them.

Field is masterful at using symbolism and central

motifs throughout the whole of the story. Windows, for example,

play an integral role, whether it is Frank Fowler looking out the window

to find Richard Strout, or whether it is the windows in the kitchen we

look through when we see a dispute erupt between the vulnerable Fowler

couple. The camerawork here, by Antonio Calvache, captures the

mood of confrontation by using a hand-held, but uses starkly realistic

montage to render a seamless illustration of pain and fear. The

music, by Thomas Newman, is sparingly used, but when it is, it

powerfully reinforces the somber atmosphere.

Like all psychologically taut masterpieces,

In

the Bedroom will invariably raise questions, discussions, and

arguments among its viewers. I feel the central theme of the movie

can be best summed up in a speech given by Strout to Natalie early in

the film: “I don’t change; the people around me change.” The film

argues that we are all capable of depraved acts of violence.

Society tells us not to act upon those impulses. But when society

fails us by letting the guilty go free and rendering justice benign, our

personal impulses are the governing dynamic in the way we act.

This is true natural law – fear and aggression, and no man-written law

can prevent it.

Above all else,

In the Bedroom takes

tremendous risks in telling its story. It offers no easy

solutions, no characters who are holistically, altruistic good or

brutally, wholly evil, but rather, characters that lie within a broad

spectrum of morality that remains unchanging even through the most

trying of circumstances. The brilliance of the film is that it is

able to portray the sympathetic Matt Fowler character as a lovable

doctor, husband, and father – but not without the capacity to be a

cold-blooded killer for the name of what he considers just. We see

Ruth Fowler as a caring and effortlessly devoted wife and mother – who

is also bitter, remorseful, and perpetually unpleased at the lack of

prudent thinking on the part of those around her. Even the

supposedly fractured marriage of Richard and Natalie can be seen in an

entirely new light in a key scene toward the end of the film, when Matt

stumbles across a certain object that would have one believe that the

Strout family was, at one point like the Fowlers, functional,

tight-knit, and happy.

I saw

In the Bedroom when I was just shy of

15 years old. I remember the occasion vividly, watching it with my

parents in a crammed theater. Afterwards, we discussed the movie.

While they liked it, even though they felt it was too depressing, it was

clear that the film had done something to me that it had not done for

them. The events of the story and the characters had taken me to

places that I could not have imagined the power of cinema ever to have

taken me before. The film transfixed me. I don’t watch it

too often for fear of seeing it too much, or familiarizing myself to too

great an extent with it. But each time I return to it, I am

constantly reminded of the power of cinema to tell a great, pure story,

and mold powerful and explosive responses from its audience. The

bridge between spectator and stage has never been so thin.

Rating:

# 1 on Top 100

# 1 of 2001

|

|

New

Reviews |

2023 PINOT BEST PICTURE

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Featured Review |

Todd #4 Most Anticipated

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Adam |

Podcast Review - Zach |

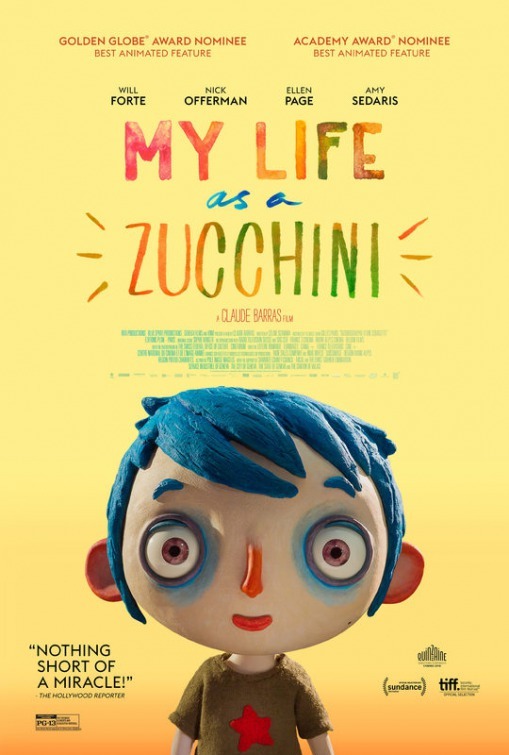

Top 10 Blindspot

Podcast Review - Adam |

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

30th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

2025 PINOTS

Nominations & Debates |

2024 Pinot Best Picture

PODCAST DEEP DIVE |

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Zach |

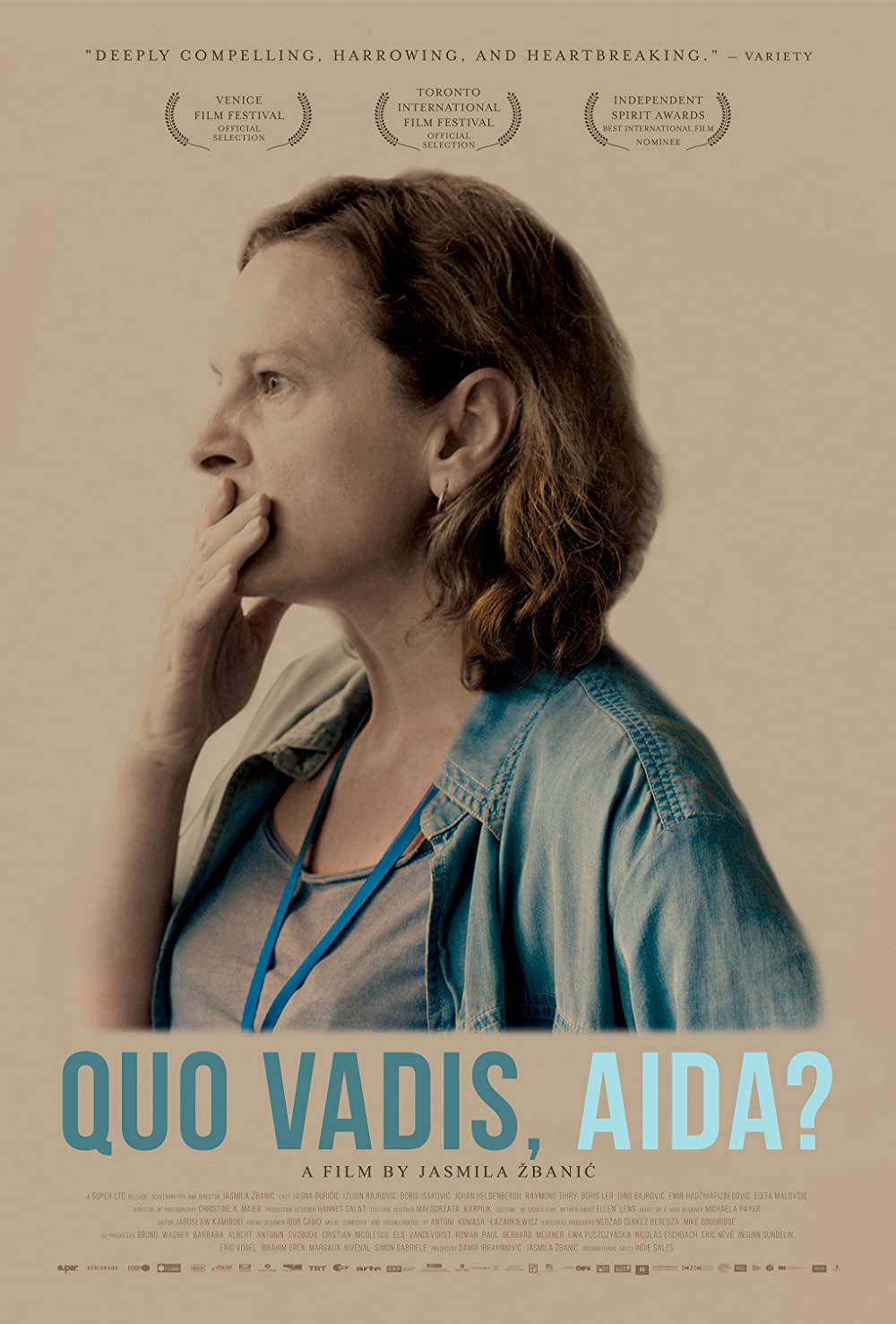

Top 10 Blindspot

Podcast Review - Adam |

10th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

20th Anniversary

Podcast Oscar Review - Terry |

Podcast Review - Zach |

TOP 10 FILMS OF 2025

LIVE ON YOUTUBE!!! |

Reactions to the Nominations

Written Article - Todd |

2026 Oscar Predictions: Final

Written Article - Todd |

Todd Most Anticipated #5

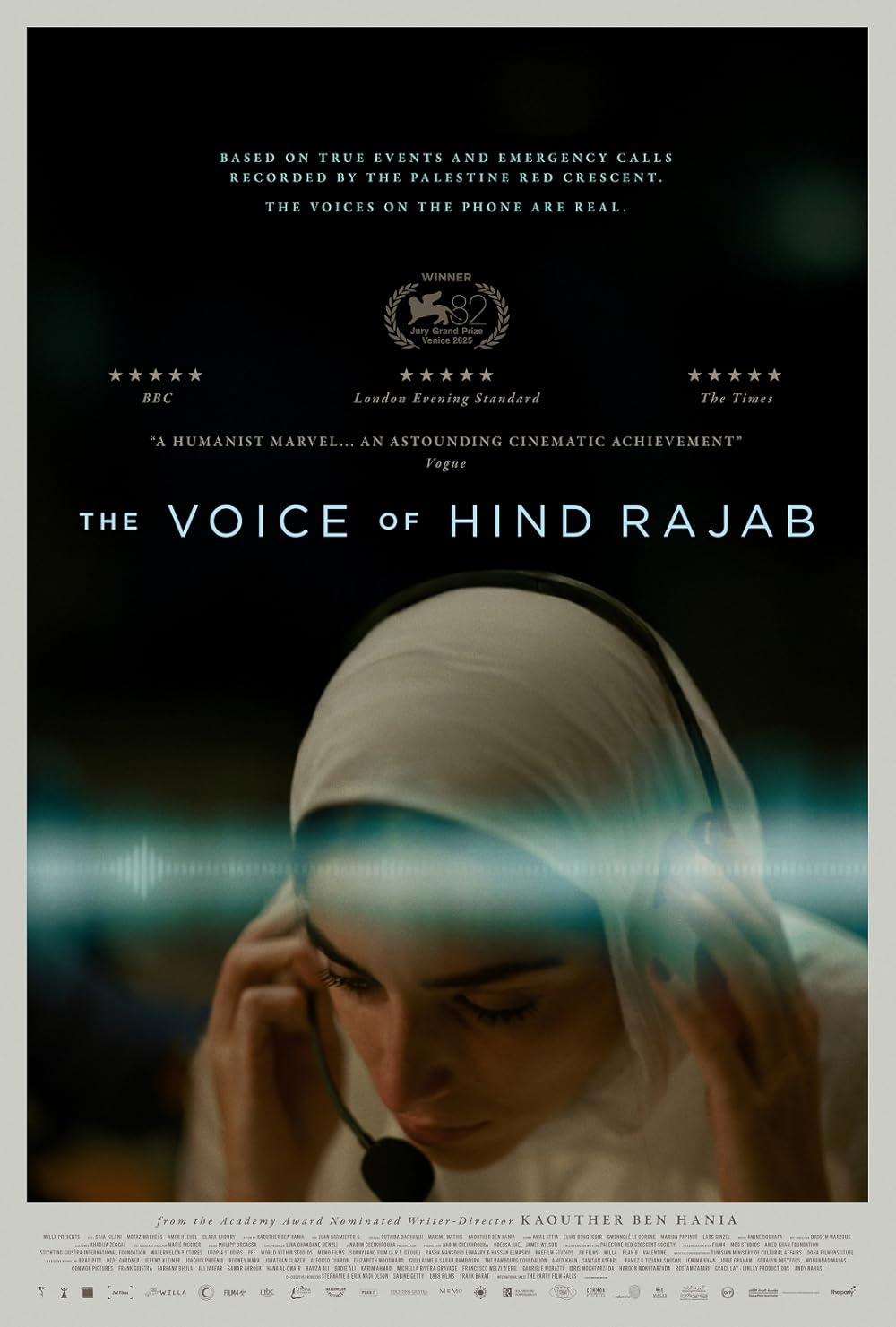

Podcast Featured Review |

Podcast Review - Todd |

Podcast Review - Terry |

|

|

|